Citing French theorist Jacques Ellul, Compact columnist Nathan Pinkoski wrote in our pages this week that propaganda “is about intensifying existing trends, getting people to act in particular ways, rather than convincing them through a new assortment of facts to believe what they hitherto rejected.” If that’s the case, last night’s Cracks in Postmodernity zine launch party was a celebration of anti-propaganda. As the curator of the literary magazine—which features content by several Compact writers—it’s my aim to provoke readers to think outside of cliched tropes and conventional polemics, in hopes of cracking through the divisive discourse (and discord) of our postmodern moment.

The party was certainly unconventional as far as New York City literary events go. We hosted it in a hotel bar in Chelsea—of all places, where a DJ spun old school R&B and reggaeton tracks, to which some danced with merriment and others tried (in vain) to talk over. I must admit being bewildered by the strange array of guests who showed up, including boomers and zoomers, people across the political spectrum, and people who had no idea what the literary “scene” was (some even asked me what “postmodernity” is). Yet if anything, it was a sign that postmodernity is indeed cracking, and that there is light (last night, a neon pink one) shining through.

This Week at Compact

Batya Ungar-Sargon started the week off highlighting “something amazing” that has happened since the last presidential debate: “Biden has come in for the kind of coordinated onslaught from the mainstream media and Democratic power brokers that is usually reserved for Republicans.” The backlash Biden is receiving from his own party is motivated not by concern over his senility, she argues, but by the fear that he won’t be able to beat Trump. She goes as far as insisting that “those of us without a high opinion of Biden’s presidency should object” as a matter of “democratic principle.”

Meanwhile across the Atlantic, French president Emanuel Macron’s call for early parliamentary elections after having dissolved the French National Assembly has resulted in him emerging as “the night’s real loser,” claims Nathan Pinkoski. Despite the Rassemblement National not having won a majority vote, “the result is short of the decisive repudiation of the far right that many pundits take it to be.” Further, Pinkoski argues, “RN’s popular-vote performance indicates a massive electoral realignment.” Distress over the future of democracy in both the US and Europe has provoked discussion over whose definition of it ought to hold most weight and which one is most accurate.

Compact columnist Darel E. Paul offers his own take on the fear spreading among the political establishments of the US, Britain, and France that recent elections are “producing dubious democratic representation.” Paul deems such reactions to the emergence of both right-wing populism and far leftism as “misplaced. Representation,” he continues, “has never been the sole purpose of elections, and it is often not even the primary one.”

You can listen to the Compact team discuss Pinkoski and Paul’s articles (as well as the prospect of a Trump vs. Biden golf match) in further depth on the Compact Podcast.

Earlier this month, Steve Bannon began his four-month prison sentence for contempt of Congress. “Bannon,” writes University of Colorado Professor Benjamin Teitelbaum, “has been pursuing two core causes: one, to tether Trump and the Republican Party to the uncompromising ideals of the original MAGA movement; the other, to unify nationalists and populists throughout the world.” Relying less on conventional forms of politicking than on tools like “podcasts, speeches, schools, and backroom meetings.” Yet Teitelbaum fears that Bannon’s time behind bars “will restrict those tools, and it comes at a time when Bannon’s causes are more vulnerable than they might appear.”

In other Trump-related fanfare, the Village Voice’s coverage of the Trump indictment is a shadow of its past sensationalistic Trump content from back in the day. Yet the alt-weekly’s fade into irrelevance is not due to its failure, argues Ryan Zickgraf, but “quite the opposite.” In his review of Tricia Romano’s The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture, Zickgraf highlights the fact that the countercultural hodgepodge of cultural and political ideas the Voice put forth from the 1960s to the 1990s has now entered into the mainstream under the guise of “progressivism,” and has been co-opted by mainstream institutions ranging from the New York Times to major corporations.

Traveling cross-country, Seneca Scott takes us to Oakland, California–just a stone’s throw from Berkeley, where Compact co-hosted a holiday party last December with Neighbors Together featuring Scott (their founder) and journalist Lee Fang. Discontent has been boiling in Oakland over its Mayor Sheng Thao. “Regular Oaklanders have had enough of rising crime and civic neglect under progressive governance,” and have voted to place a recall referendum on the mayor. Though Thao and her supporters chock the 40,000 plus signatures backing the referendum to the efforts of “right-wing extremism,” in reality Scott says it’s been driven by a “remarkably post-partisan grassroots movement” led by “ordinary people who just want the city to function properly.”

Closing out this week, Michael S. Kochin makes a provocative argument for the separation of science and state, taking his cues from the classical liberal argument for the separation of church and state. Just as elected officials shouldn’t “demand deference to religious authorities such as Pope Francis, Li Hongzhi, the Universal House of Justice, or L. Ron Hubbard,” they also shouldn’t “act in their official capacities as followers of ‘the science’...Scientists, like religionists,” Kochin argues, “are free to try to persuade others with arguments and insights they have derived from their sect or laboratory, but they should be ignored when they demand that outsiders defer to them as authorities.

Some recommendations

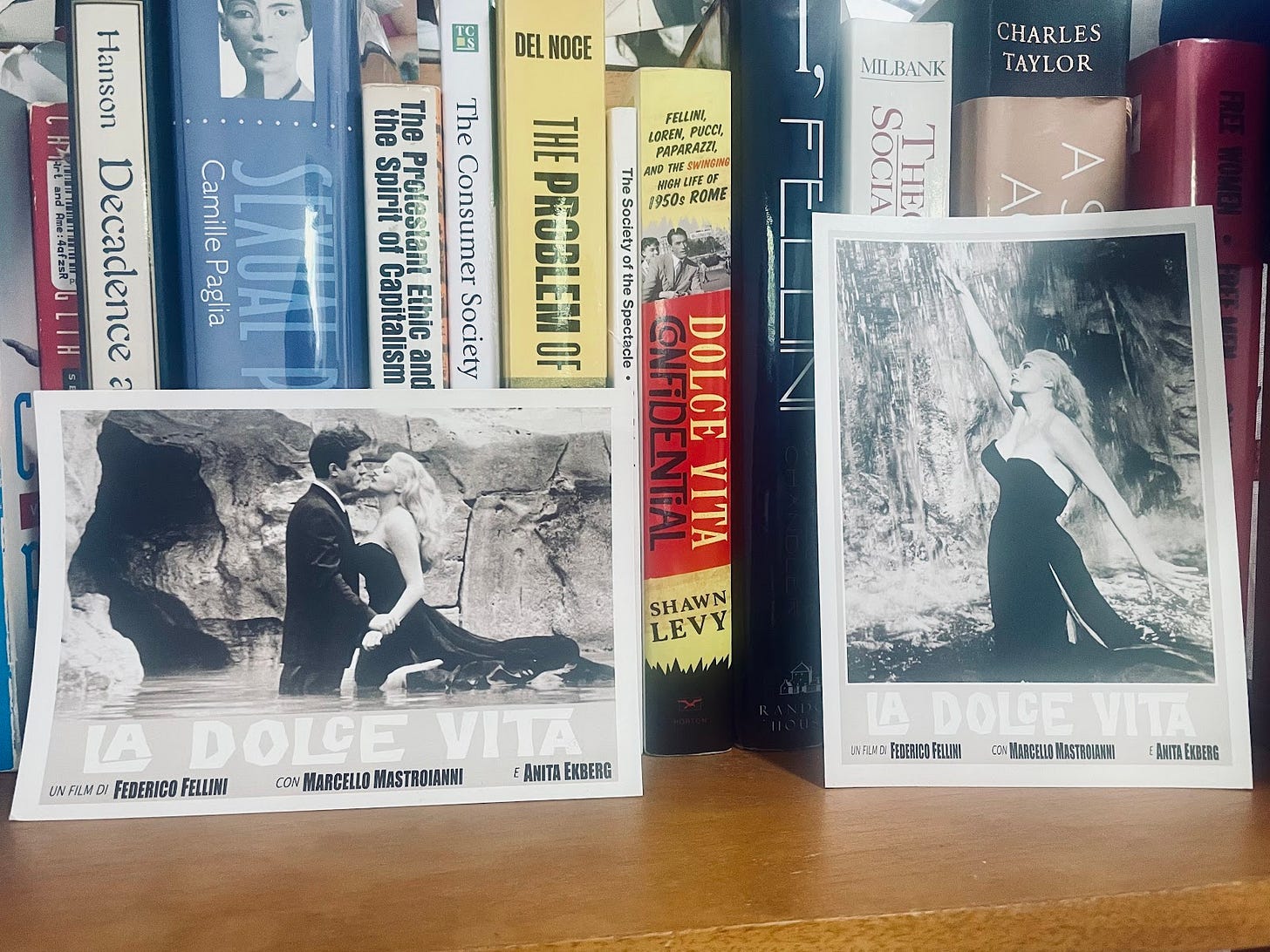

Shawn Levy’s book Dolce Vita Confidential has been a nice break from–and helpful to read alongside–more theory-based texts I’ve been reading by Guy Debord and Jean Baudrillard. The book covers “the swinging high life of 1950s Rome,” using Fellini’s film as a springboard to investigate the shifts in fashion, morals, culture, and economy in post-war Italy. Levy depicts some of the real-life episodes which inspired scenes in the film (namely, Anita Ekberg taking a dip in the Trevi Fountain after a long hot evening on the town, and the sensational media coverage of the Virgin Mary’s appearance in an Umbrian village), asserting that La Dolce Vita is an example of “art imitating life which imitates art.”

He went on to describe how the film drew international attention to Rome’s star-studded Via Veneto, which the film “built” both literally and figuratively. Though the street was already a hot spot for celebrities, paparazzi, and wannabes before the release of the film, Fellini’s mythologization of it expanded its reality to even grander proportions–attracting celebrities from around the world and tourists thirsting for a taste of the “sweet life.”

But in reality, most of the film’s scenes in Via Veneto were actually shot on a replica of the street on set at Cinecittà (Fellini received permission to shoot a very brief scene on the actual street). I couldn’t help but recognize the film’s link to Debord’s theory of “the spectacular society,” which glorifies spectacles that are “all surface” and hollowed out of depth and meaning, as well as to Baudrillard’s insistence that we are surrounded by “simulations” whose “referentials” to reality are increasingly weakening.

Despite Fellini’s insistence that the film was meant to be more of an exploration of the complexity of modern life than a polemic, it scandalized both the left and right upon its release in 1960. Marxists critiqued it for veering too far away from the proletarian commitments of neorealist cinema. And the Vatican condemned it as “highly corrosive” for inciting young people to glorify an “easy, materialistic life without ideals,” and called for “projects of this kind [to] be crushed immediately.”

The film, much like Fellini himself, was misunderstood. Levy does his best to capture Fellini’s playful and unpredictable yet equally humble and endearing persona, citing some of his quirkier quips, including his take on the term “felliniesque” being added to the dictionary: “I always dreamed of becoming an adjective when I grew up!” Dare we hope for more “felliniesque” figures in today’s polarized landscape full of pundits whose views at times feel algorithmically-generated.

Dreaming of becoming an adjective, like Fellini! :) That's why my preferred pronoun is an adjective: "altaiflandesque."