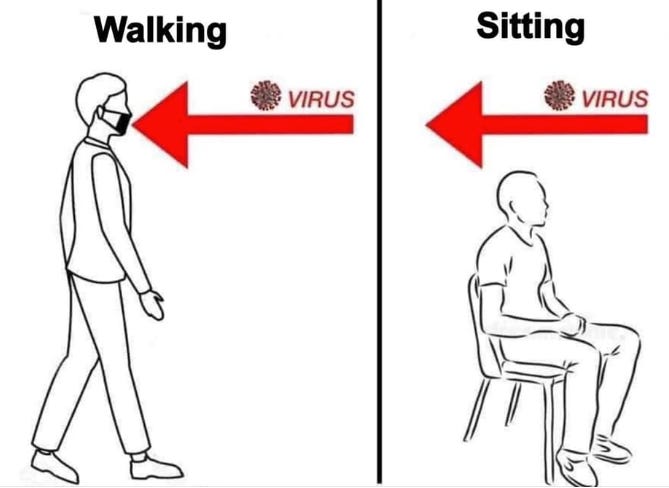

The other evening, I walked past a restaurant and saw a young woman sitting alone at a table by the window, wearing an N-95 mask. Presumably she went on to remove the mask when her food arrived. A few blocks down, I walked past a restaurant that still had a “no mask, no entry” sticker on the door. I was reminded of the circa 2021-22 mandatory ritual of masking between the entrance of a restaurant or bar and your table, immortalized by this meme:

In recent days, I also noticed a few people on the subway still masking—almost all of them, though, with their masks sagging below the nose, in one case just below the mouth as well. While for some people, perma-masking is clearly a political statement or a reflection of their undying fear of contracting long Covid, it’s hard to imagine this is the case for the perfunctory below-the-nose perma-maskers. So what is going on with them? Such behavior made sense when mandates were in place—indeed, I masked below the nose myself a few times so as to keep breathing normally when under obligation from the authorities. I have no idea why people under no obligation to mask would do so in such a way as to enjoy none of the supposed protection it offers.

Covid was on my mind this week because we are marking the fifth anniversary of lockdown, and also because I reviewed Stephen Macedo and Frances Lee’s In Covid’s Wake for the Chronicle earlier this week. Macedo and Lee (who made the case for Jay Bhattacharya to lead NIH in Compact last November) offer perhaps the most comprehensive indictment of the Covid-era public-health regime to date, and do so as impeccably credentialed liberals. I hope the book will be widely read and discussed, especially among those with an influence on Democratic politics. There are reasons to be worried about RFK’s influence on health policy, but for liberals to negatively polarize themselves back into Covid-era dogmatism would be, in my view, an even greater disaster. Fortunately, my impression is that the liberal consensus is slowly shifting to a recognition of the harms and excesses of many policies in that era—that the critical angle articulated by The New York Times’s David Leonhardt while many of the policies were still in effect, to considerable controversy at the time, has gradually won out

That isn’t to say the lockdown and mandate regime doesn’t have some last-ditch defenders, just as masking has some last-ditch practitioners. As far as I can tell, those stalwarts are entirely on the progressive, mostly academic left. I was reminded of their existence when Tyler Austin Harper, an Atlantic columnist and professor at Bates College, praised Macedo and Lee’s book on X. He was in turn denounced by, among others, Beatrice Adler-Bolton, co-author of the 2023 book Health Communism (reviewed by Leila Mechoui here). Adler-Bolton’s objections made me recall the left argument for lockdown, which I’d somewhat forgotten about but was widely advanced during the first year or so of Covid. In her words: “Public health measures protected all workers, capitalists pushed to dismantle them.” Lockdowns and mandates, by this account, placed “health” above profit, and were thus a blow to the capitalist system; anyone who opposed them was doing so on behalf of capitalists who wished to sacrifice workers on the altar of profit.

The most obvious objection to this line of thinking is that a large portion of workers did not, and could not, stay home without the result being total breakdown of the basic functions of society, and were thus not “protected” by stay-at-home orders. The response, as articulated by another left academic who criticized Austin’s post and was in turn retweeted by Adler-Bolton, is that “large numbers of workers staying home protect those that are made to work in person by lowering overall transmission.” One could quibble with this on several fronts. For one thing, it isn’t clear from the numbers that this really happened in any consistent way; for another, the goal of indefinitely “lower[ing] transmission” overall is questionable in itself. But rather than relitigating those points, I’d rather focus here on the basic left-covidian premise that pandemic-era public-health measures were pro-worker and anti-capitalist. We heard this endlessly in 2020-21: if you were in favor of reopening, you were accused of prioritizing “the economy” over human life and health. (Since in that period, the only threat to human life and health was one particular virus and not, say, prolonged isolation.)

If you share the Marxian assumptions of someone like Adler-Bolton, one would think it would be quite surprising if lockdowns and mandates were in fact pro-worker, anti-capitalist measures, consider they were implemented with gusto by unquestionably pro-capitalist governments of left, right, and center around the world. In the specific context of the United States, to be sure, opposition to Covid policies quickly became right-coded, although any leftist could tell you Andrew Cuomo isn’t a pro-worker or anti-capitalist politician. But the idea of lockdowns as a progressive cause—which many on the US right also seem to assume—collapses once if you look at Covid policies as a global phenomenon. For one thing, right-wing governments in countries including Hungary, Israel, and El Salvador enforced far stricter stay-at-home orders than any Democratic-run US state; and all manner of unambiguously neoliberal center-right governments around the world did the same.

Did all of these politicians and parties suddenly embrace aggressively pro-worker policies that antagonized capital because they accidentally became “health communists” for a year or two before reverting to their priors? It seems to me that the safer Marxist assumption would be that if nearly every government in the world, none of which could be reasonably described as run by pro-worker parties, embraced a policy, that policy was probably not, in fact, pro-worker and anti-capitalist. I imagine the left-lockdowner response would be to claim that workers effectively agitated for safety, and perhaps in a few limited cases, such as blue-state teachers unions, there isn’t nothing to this. But we’d then have to ask how workers gained a leverage they haven’t had in any other struggle for many decades. In any case, the initial timeline of lockdown simply doesn’t support the claim at all; for instance, the World Health Organization, which was crucial in prevailing on governments to adopt the Chinese model, isn’t exactly a locus of working-class power.

So why do so many on the left continue to believe to this day that policies imposed by the global ruling class—including such bugbears as Netanyahu, Orbán, and Bukele, (and even Donald Trump himself, who at first supported lockdown)—comprised a revolutionary anti-capitalist project? While contemplating this enigma, I was reminded of Anton Jäger’s March 25, 2020 essay in Damage, “It might take a while before history starts again.” As Jäger noted, one of the most remarkable things about the Covid crisis was how quickly it sidelined the basic framing of politics that had mobilized left populism over the prior decade: the struggle against austerity. With even Republican and Tory governments as well as the European Union rushing to expand the social safety net, send out checks to citizens, and carry out quantitative easing on a scale never seen before, the cause that had defined left-wing politics throughout the 2010s—in effect, defending the humane side of the state from neoliberal depredations—abruptly became obsolete.

Jäger went on to observe the tragic irony of this situation: “The left’s real trauma might be that neoliberalism died without them actually killing it. The left waited for ten years for someone to finally bury the neoliberal settlement; no one arose, and now an extra-human agent will take care of it.” Perhaps, then, the left can’t let go of Covid because the virus was a more efficacious version of itself, a sort of ego ideal—that is, it was the force that actually succeeded in slaying the dragon of neoliberal austerity. But in its interminable mourning of the supposed anti-capitalist policies it believes somehow came into place during those years, it has in effect resigned itself to its own impotence. The positions many on the left still seem to hold—apparently, that society should remain locked down until Zero Covid has been achieved—are such an obvious political dead end that I haven’t seen any of their preferred politicians attempt to present them as a positive agenda. But this, perhaps, is the point: If your politics are utterly unviable, the best you can do is await the next miraculous emergency that will allow “pro-worker” policies to be enacted in the absence of a workers’ movement.

This week in Compact

Peter Hitchens refutes Douglas Murray’s j’accuse against Ukraine war skeptics

Peter Ryan explains the real reason Trump has become a crypto booster (hint: it’s not just because it will enrich his friends, although it may do that too)

Batya Ungar-Sargon argues that behind all the economic turmoil of recent weeks, Trump does have a plan to radically restructure the US economy

Leila Mechoui explains why Canada is in a weak position in the trade war

Thomas Fazi examines the latest developments in Romania, whose US, EU, and NATO-backed regime will stop at nothing to prevent a populist from taking power

Tim Gill offers a nuanced take on the track record of USAID

GD Dess uncovers the sexual conservatism of an outspoken progressive novelist

Hamilton Craig situates the arrest of Mahmoud Khalil in longer historical context

During the mask mandates, I’d estimate that 99% of people wore masks, and about 75% wore them correctly. After the mask mandates were lifted, about 15% still wore masks, and at least 80% of them wrong them incorrectly. Which meant that those most wanting to wear masks had absolutely no idea how they were supposed to work or what they were supposed to be doing.