Holy Week in this often less-than-beautiful part of South East London, yet if you focus on the green and yellow rather than the concrete, it all seems a little more…well, alive. While the Spring weather enters its adolescence, storming about, punctuated by moments of brightness, the rain is overall less a watery prison than the promise of clarity to come. And it makes the green of the plants and trees greener…

Lately I have been thinking about friendship. In the age of identity, friendship remains a mysterious thing: valuable precisely because (in the best cases) there’s no point to it. Aristotle identified three kinds of friendship: those that are useful, those that are fun, and those that are virtuous, or friendships of the good, based on mutual admiration and respect. This can take the form, to my mind, of a shared intellectual dialogue, a shared interest in culture and critique, as well as a shared interest in understanding what the “good” is, and so on. Often, of course, these distinctions are not always clear: a friendship that becomes a business partnership will include elements of exchange, even where the motive for working together is qualitative; a friendship based on shared (positive) values will also (hopefully) be enjoyable.

But friendship is often mysterious. It lacks the solidity and public recognition of a romantic relationship or marriage. There are no ties of blood, as with family. It occupies a hazy grey zone, and sometimes we make up “objective” reasons why we must stay in touch with someone, because to admit to wanting to do so merely on the basis that one would like to seems potentially embarrassing. It’s usually impossible to know the extent to which you feature in someone else’s life, and often there is an anxiety around any imbalance: what if I’m more friends with this person than they are with me?

In Holy Week the question of friendship and betrayal is clearly posed: Jesus bathes the feet of his friends, who are also disciples, in an act of humility; Jesus is meanwhile betrayed by Judas. The mob who loved Jesus turns against him in a matter of hours. We’ve all been friend, betrayer, mob. It’s easier to remember when we’ve been betrayed than when we ourselves have betrayed—at which point our mind goes strangely blank. It is at that point we play down our significance in someone else’s life.

Contemporary life is full of half-friendships: relationships left hanging, people denouncing one another over differences of opinion, or because one person is friends with someone else who the other dislikes. The uncertainty and ambiguity of friendship continues long into post-friendship. I’m not sure I’ve learned anything definitive about friendship, other than the recognition that you’re lucky if you have any at all, and probably two or three is about right. One cannot truly like that many people; nor can one in turn be liked by many either. Basic politeness is highly useful in this regard, because most of our relationships will remain at the level of friendly acquaintance, but not “true friendship.” Georges Bataille describes friendship in the context of meaning. The “private being” he conceptualizes should serve, perhaps, in the context of an age of atomization, identity and convenience, as something of a warning.

My conduct with my friends is motivated: each being is, I believe, incapable on his own, of going to the end of being. If he tries, he is submerged within a ‘private being’ which has meaning only for himself. Now there is no meaning for a lone individual: being alone would of itself reject the ‘private being’ if it saw it as such (if I wish my life to have meaning for me, it is necessary that it have meaning for others: no one would dare give to life a meaning which he alone would perceive, from which life in its entirety would escape, except within himself).

Latest pieces in Compact

This week we published Arta Moeini on Ukraine. Tensions over funding and support in Europe, and between parties in power and anti-war opposition parties have reached, Moeini argues, an inflection point. Nevertheless, there is a deeper motive: “Lurking beneath the clamor for European unity is a political struggle to establish supranational EU sovereignty—a project that trumps all other considerations, including Europe’s own strategic autonomy.”

Justin Vassallo wrote for us this week about potential obstacles to “a broader organizing wave gaining momentum in the service sector.” In an in-depth and by no means pessimistic—although certainly realistic—account, Vassallo notes that “if, as a society, we are to still enjoy some of our modern conveniences and daily luxuries, new policies will have to be introduced alongside greater enforcement of existing labor laws.”

Juan David Rojas analyses the relationship between the Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) and Donald Trump, particularly around what might seem to be different positions on immigration from Mexico to the US: “the cooperation achieved by AMLO and Trump shows that Mexican and US interests on immigration can overlap to some degree.”

Finally, we have Compact editor and cofounder Sohrab Ahmari’s vital piece “The Passion of Artsakh.” As he puts it, his account is “based on extensive interviews with the women conducted across Armenia proper, this narrative amounts to the first public oral history of one of the clearest cases of 21st-century ethnic cleansing, carried out in broad daylight and with minimal protest from Western capitals. Their stories present a harrowing study of what it’s like to lose a home and a community in a flash of days. They also attest to the resilience of the Armenian people—and to the indomitable spirit of women in wartime.” This Easter weekend, do turn your attention to this tragic and overlooked story.

Nina Recommends

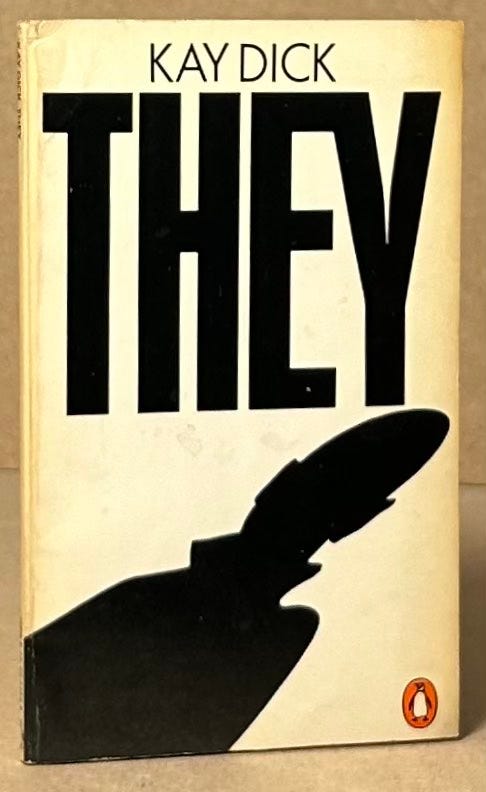

This week I read Kay Dick’s They, a strange, short dystopian novel from 1977 that was lost for many years until a chance encounter in 2020 between a literary agent and a charity shop. Dick (1915-2001) was a popular writer, editor and director of a publishing house during her lifetime, but They quickly went out of print. It was described at the time by a Sunday Times reviewer as “a fantasy sprouting from some collective menopausal spasm in the national unconscious.” While this sounds amazing, I’m not sure it’s accurate.

The novel is, though, very disturbing. Some largely unseen force is destroying art, and stealing books from people’s houses. People are being taken away and their emotions wiped, returned only so they can watch television. Grief is punishable by the authorities. Anyone who lives alone or is unconventional in any way is a target. Random acts of violence occur among the people. There are shades of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 as people try to remember poems and keep the lost art of writing alive through letters: “On the way back to my cottage I tested my memory of Henry James’s later novels”; “Shelley’s poems and Katherine Mansfield’s Journals were missing.” As an unintentional account of memory-loss in the age of outsourced data and censorship in the age of streaming-platforms and bookshop workers hiding books they don’t like, it’s prescient. Characters appear and disappear and the censors or moral police, whoever They are, seem all the more menacing because barely described. Meanwhile, people continue to talk, walk outside, and play with their dogs. Flowers continue to grow. We live!

Until next week - Nina

I have a feeling your mind doesn’t quite go “blank” the same way mine does...