From the War on Terror to the War on Covid—and Back Again

Meet the new state of exception, same as the old state of exception

A good deal of my writing in the years 2020-22 involved revisiting material I had studied in graduate school in a particular historical moment—the final years of George W. Bush’s administration and the first years of Barack Obama’s—and applying it to a new moment, that of the pandemic and its political fallout, which both resembled the prior one and did not.

The Covid era resembled the post-9/11 one in that an emergency had led to the declaration of a state of exception, which in turn led to massive infringements of civil liberties. It didn’t resemble it in that the political sides were almost completely reversed in how they responded to this situation, with the left largely cheering on emergency politics and the right opposed, as I wrote about at length. At the time, I was interested in: 1) reminding people on the left of the philosophical arguments they had made against Bush’s War on Terror amid the War on Covid; 2) trying to offer a more in-depth, nuanced version of these arguments to readers on the right than was available.

In recent weeks I’ve found myself returning yet again to the same themes, the ones Giorgio Agamben captured in the subheading of Homo Sacer: “sovereign power and bare life.” Rather than exhaustively explain the renewed relevance of these ideas, I will quote at length from something I wrote in 2022, a speculation about where emergency politics would go after Covid:

In his books Homo Sacer (1995) and State of Exception (2003), Agamben examines a paradox at the core of political sovereignty. The sovereign authority that instates and grounds the rule of law, he observes, must also be empowered to suspend it. The suspension of law occurs, most obviously, when a crisis leads the authority to assume emergency powers that bypass normal procedures and constraints. Following the Weimar-era right-wing jurist Carl Schmitt’s dictum that “sovereign is he who decides on the state of exception,” Agamben concludes that sovereignty must be located outside of the law that it sustains. What guarantees the law also stands outside of it. The state of exception, in this sense, always hovers behind the normal rule of law.

The second key concept for Agamben’s argument is “bare life,” understood as the pure biological functioning of the human organism. In the ancient conception articulated by Aristotle, “bare life” stood outside of politics, which was concerned instead with the “good life.” But Agamben argues that what is distinctive to modern politics is the extensive involvement of political power with the “bare life” of citizens — what Michel Foucault called “biopower.” With the emergence of biopower, what in classical thought had been excluded from politics — mere biological life — becomes the primary object of the exercise of power.

For Aristotle, the law, which orders the polis, enables the transcendence of bare life and the pursuit of the good life. For Agamben, the state of exception, which is the law’s necessary precondition, reduces the citizen to bare life: The suspension of the law facilitates the direct exercise of sovereign power over human beings, now stripped of the protection of the law and deprived of the substantive goods of the polis. Hence, Agamben interprets the modern rise of biopower as a permanent state of exception, the full realization of which could be found in the Nazi concentration camps.

Further on in the same essay, I argued that:

the anti-exception politics of the Covid era risks maintaining the fundamental framing of the regime it opposes. There is clear recent precedent for this. Those on the left who opposed Bush’s War on Terror regarded national security as the embodiment of sovereign power exercised outside the rule of law. Later, many of the same figures embraced the same security agencies as a bulwark against Trumpism, and fomented a panic about far-right domestic terrorism that echoed post-9/11 rhetoric on the right. Similarly, those currently positioning themselves against the Covid state of emergency may be just as likely to perpetuate a mode of governance that authorizes itself in the looming threat of a future emergency.

Three months into the new administration, I can only say I’ve probably never written anything that has been so thoroughly vindicated. Probably naïvely, and as I’ve said before, I found it possible for a time to imagine a more “normal” Trump administration than what we are getting. To that extent, I was wrong, and should have trusted my instincts from 2022 or so.

What has been interesting since the beginning of Trump 2.0 has been the conversion of nearly every realm of politics into emergency politics. Even in the normally humdrum, wonkish realm of trade policy, Trump’s radical tariff agenda was justified on the basis of an ostensible national emergency. Meanwhile, there is a massive ramping up of the same rhetoric that drove the War on Terror. Immigration enforcement and crackdowns on campus protest are framed as “anti-terrorist” actions, deportations are justified on the basis that criminal migrants comprise an invading army, and so on. A new Guantánamo, of comparably ambiguous legal status, has sprung up in Nayib Bukele’s El Salvador, a country whose recent history reveals the continuity between pandemic states of exception and the expansive new "anti-terrorist" agenda. I believe one of Agamben’s dictums helps us understand the role of Bukele’s CECOT in the new American political reality: “The camp is the space that is opened when the state of exception begins to become the rule.”

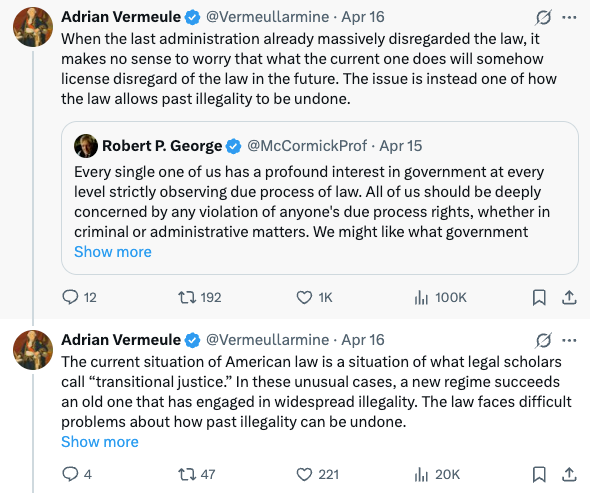

In the case of 9/11 and Covid, a sudden exogenous shock made the state of exception possible. When it comes to the current situation, it is oddly Trump himself who is the exogenous shock as well as the sovereign declaring the state of exception. In the post-2016 era, Trump himself was framed by the establishment as the emergency against which the state of exception needed to be declared. As I wrote in 2022, “liberals in the [first] Trump era arguably saw themselves not as resisting a state of emergency imposed upon them, as they did under Bush, but rather as the ones declaring it, with their protestations of ‘this is not normal!’” Now, you see Trump and his supporters arguing that the lawlessness of Biden’s administration (in failing to enforce borders) may well require an equal and opposite disregard for norms procedures in order to reimpose order. At least that’s how I parse this:

It isn’t difficult for me to imagine a defender of some of the Biden administration’s post-2020 actions advancing a similar argument. And perhaps that’s the point, and entirely to be expected. As I wrote in 2022:

Those who resist the state of exception may believe that if they do so fervently enough, we can return to some state of normality. But all of the most influential elaborations of the concept suggest that exceptionality will always persist to some extent as a foundation of power.

The only remaining question, if so, is to what extent…

This week in Compact

Ralph Leonard on how Trump’s GOP became the party of the future

James Hankins on why Trump should use the NEH rather than abolishing it

Me on why Mario Vargas Llosa was perhaps the only great neoliberal novelist

Philip Cunliffe on a new history of weird strains of libertarianism

Patrick Brown on the red states making progress on populist family policy

Sam Kahn on why Gavin Newsom’s podcast is good, actually

Lisa McKenzie on why the working class needs jobs, not therapy

Thanks for reading!

Superb. Where else could you go to read something like this? Nowhere, because no one else is putting these pieces together. Helps us see the moment we’re in clearly, and further traces the realignment’s history.