Spring is here…And Compact is two years old today! The founding editors asked me to join them as a senior editor a few weeks after launch—and it’s been absolutely wonderful. I’m proud to work with such honorable and dedicated men on the best magazine around. To the common good!

In the wake of the launch of Blame Theory (and there’s a special episode on Judith Butler out today—whose new book Who’s Afraid of Gender? and the trajectory of her thought since the early 1990s is singularly appropriate for a reflection of “blame”—has just come out), I’ve been thinking about “progress.” We find ourselves constantly reflecting on our Christian inheritance and the extent to which we retain religious modes of behavior, and whether the new morality is a version of secularized Christianity without forgiveness, and so on.

Christopher Lasch’s The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics (1991) stresses instead what he sees at the “profound differeces” between the Christian view of history and “the modern conception of progress.” The latter, he suggests, is not after a secular utopia (“heaven on earth”) that would “bring history to a happy ending” but rather “the promise of steady improvement with no foreseeable ending at all.” This worldview takes its cue from science rather than religion: “A social order founded on science, with its unnerving but exhilarating expansion of our intellectual horizons, seems to have achieved a kind of immortality undreamed of by earlier civilizations.”

The past few years have demonstrated the way in which bad, or let’s say hysterical, science has become an object of worship across the political spectrum. To take two different examples, while lockdown-supporters, often extremely cruel in their attitude towards dissenters, uncritically trusted “the science,” various rogue ideas from evolutionary psychology, such as hypergamy—the idea that women seek to marry “up” the better to provide resources for any children—have become entirely detached from any context, taken up as cudgels to beat one or the other sex with. Critical concern with the fit between theories and the reality they seek to describe is often lost in the bid to explain at all costs.

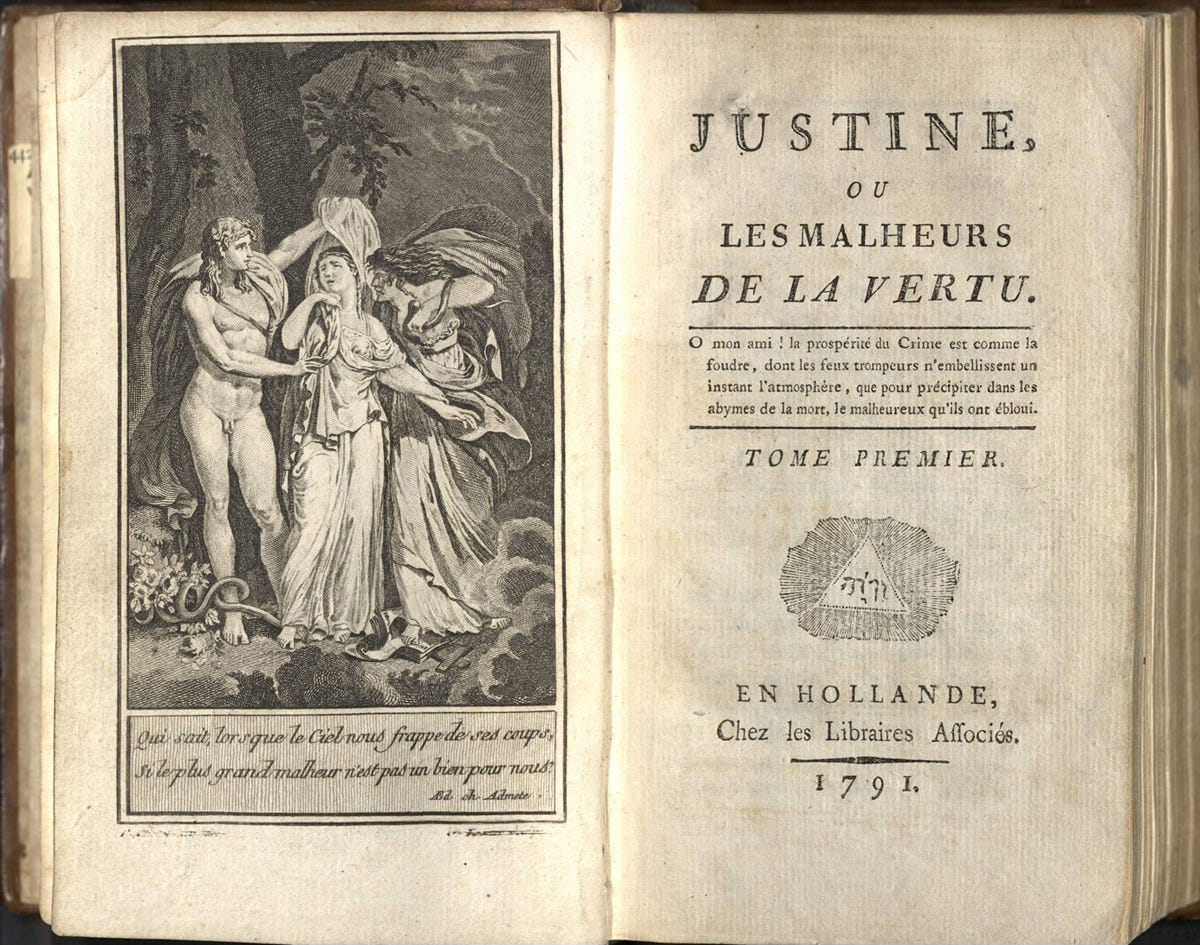

The commitment to progress-without-end, even in the face of disaster—human and natural alike—has terrible consequences for the social good. Whether it be Andrea Long Chu’s recent call for children to be able to “change sex” (an impossibility of course) at will—an admission that transgenderism is merely the culmination of the libertine project best embodied by the Marquis de Sade for whom sodomy was an (im)moral duty—or the Silicon Valley obsession with eternal youth and immortality, there are few powerful people content to accept what Lasch calls the “moral realism” of “lower-middle class culture” which respects limits and understands that “everything has its price” and that promises of progress should be treated with skepticism. The unpopularity of saying “hang on a minute” has seen many, left and right, punished—but we need this perspective more than ever: The idea that we know what everything is for, let alone the desire to change it before we do, is pride on a catastrophic scale.

Latest pieces in Compact

This week founding editor Matthew Schmitz responds to the “bloodbath” controversy of Trump’s recent Ohio speech, pointing out that “the ‘bloodbath’ comment came in the midst of a discussion of US trade policy.” What the predictable media response shows, Schmitz suggests, is the importance of Trump picking a good running mate: “He will need an ally who is ready and able to push back against distortions in the media, while also fully supporting Trump’s agenda on trade, immigration, and foreign policy.”

Continuing our in-depth coverage of South America, Juan David Rojas discusses the ties between Honduras and the United States in the wake of the former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández’s conviction for drug trafficking and weapons charges in New York. Rojas notes: “The other lesson of the Hernández affair is that efforts to rein in the power of organized narcotics syndicates won’t bear fruit so long as policymakers insist on combining anti-drug policy with ideological meddling in regional affairs.”

Frank Furedi positively reviews Abigail Shrier’s much-discussed new book Bad Therapy, discussing the “influence of a broader therapeutic culture that unwittingly incites people to feel ill.” Furedi argues that “The main driver of the medicalization of childhood was the displacement of traditional modes of socialization with one that was oriented toward the promotion of psychological values.” The shifts in the past 45 years (which predate social media, often uniquely blamed for unhappiness, particularly in the young), have been crazy. I remember when the first wave of SSRIs started being prescribed in the 1990s (preceded by the contraceptive pill as “better living through chemistry”). There’s no doubt that normal human feeling, such as grief or energetic behavior among the young, particularly boys, has been pathologized. Puberty is difficult for pretty much everyone, but it’s not a medical condition: To never confront difficulties and overcome and learn from them is to generate new suffering in the form of anxiety: the therapeutic/medical culture is often a vicious circle. Bring back ritual markers and the wisdom of elders!

Speaking of better living through chemistry, Leila Mechoui reviews Benjamin Breen’s Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of Psychedelic Science, noting that, ultimately, “the counterculture wasn’t so much a spontaneous youth rebellion as the popularization of a worldview initially disseminated, top-down, by a group of institutionally protected elites.”

Tano Santos and Luigi Zingales look in-depth at the relationship between Big Tech and Democracy, arguing that “digital networks live outside society, so to speak; they propose another society, and they aim to substitute for the array of physical networks we live in.” But rather than give into a kind of techno-determinist despair, the authors propose a series of measures to democratize technology itself, suggesting practical ways in which technological advancement can be placed in the service of local democracy.

Darel E. Paul analyses what he calls “the Permanent Sexual Revolution,” making a welcome Laschian argument, namely that “the moral and political project of the Permanent Sexual Revolution can be summed up as the establishment of sexuality as a sphere of liberty.” This project is in full swing. Paul notes that “while social morality before the revolution restrained childless adults who might express sexual values openly hostile to family formation, there are no such reins today.” We truly do live in the libertine’s world, but as Paul notes, shocks such as the Irish voting against eliminating the words “women” and “mother” from their constitution are positive signs: they will call those say “hang on a minute” reactionaries and worse until the cows will come home. But the cows (and milk) remain, despite the best efforts of Big Almond to convince us otherwise.

Next up, it’s Ashley Frawley on the recent WPATH revelations: “As the rise and fall of diagnoses like DID and others before and after it tell us, the self is incredibly malleable. We desperately search for something we can hold onto, an identity as innate and easily fixable as a pancreas or a heart valve, but though our bodies are the same as those of our ancient ancestors, the psyches inhabiting them are profoundly different.”

And finally, our weekend read is novelist Jordan Castro on the irritating habits of the academic class: “A professor must spend his entire life trying to please others—first his own professors, then his doctoral adviser, then his tenure-review committee, then his scholarly audience.”

Nina Recommends

I saw the packed-out UK premiere of Sir James MacMillan’s Fiat Lux at the Barbican conducted by the man himself. The work for chorus, orchestra, organ and soprano and baritone soloists was written to mark the consecration of Christ Cathedral Garden Grove in California, and is based on a poem by Dana Gioia. MacMillan is one of our great contemporary composers (and conductors), and his faith shines through all his work. Fiat Lux made me think of Coventry Cathedral (the new one), and the relationship more broadly between modernism and Christianity in the wake of senseless, mechanistic destruction.

The night after I saw a reading of (part of) Goethe’s Faust in London’s oldest surviving church, St Bartholomew the Great, which celebrated its 900th anniversary in 2023. A daring place for The Base Creates to host Mephistopheles (played by Oliver Bennett), but the metaphysical dance of despair, temptation, worldly desire and the little black poodle of evil was vivacious and relevant. Sebastian Milbank gave a historical and conceptual response which noted the on-going importance of redemption in any understanding of Goethe’s work. It is truly wonderful to see life return to a culture that has become somewhat rigid in recent years. Let there be light.

Until next week! - Nina