Suddenly everything is alive again: Social life reawakens alongside the emergent daffodils and snowdrops. While mad ideas continue their long march through the institutions—and it will take a while to roll back HR initiatives no doubt—there is a renewed optimism (in me, at least) that interesting conversations are possible again. The constant anxiety about saying the wrong thing or being friends with someone that others may disapprove of seems to be receding as people understand once again that there is no Big Other, at least not a human one: the onus is on us to think and feel for ourselves. No more “Be Kind!” posters (these were plastered all over London during the catastrophic lockdowns). Constant self-policing is tiring and, above all, boring. Life is complicated: great dialogue and art reflects that.

I’ll be in in New York next week for the launch of a new podcast—Blame Theory—alongside my colleague Geoff Shullenberger. Blaming a thinker or a worldview—Plato, Hegel, Kant, the Enlightenment, feminism, postmodernism—for everything that’s gone wrong, is a common contemporary move. On each episode of the show, whether the topic of discussion really is guilty for all the ills laid to its charge, with levity and seriousness. We’re recording the first episode live with Professor Avital Ronell on Thursday 29th February on the topic “Blame Postmodernism”. There are a few tickets left, available here. I’m looking forward to seeing New York again (albeit briefly): let me know here if there are any exhibitions I should visit!

Latest pieces in Compact

Geoff continued his quest to understand what makes El Salvador tick under Bukele, noting “Before the state of exception, the gangs were everywhere, extorting, terrorizing, harassing, and killing; now they are not. Amid the new freedom from fear, aspirations have become possible that were not before.” Bukele’s political orientation not straightforwardly the pro-order right-wing position it might seem, and Geoff’s essay carefully unpicks Bukele’s perhaps surprising debt to the Latin American left: “the critique of imperial meddling in the country’s internal affairs, the grievances against Washington, the call for sovereignty and freedom.”

Another game of chess, my dear? Leo Tolstoy and his wife, Sofia Andreyevna Tolstoya by Ilya Repin

Valerie Stivers wrote about Tolstoy’s unusual recommendation for married couples, as presented in his short story “The Kreutzer Sonata.” This is a great article to read in the context of Lent and to remind ourselves that we often confuse abstinence (total avoidance, married or unmarried), chastity (controlled sexuality, i.e. sex within marriage only) and celibacy (unmarried therefore no sex). There’s also continence, which rarely refers to sex these days.

When researching online male communities for What Do Men Want? I found the NoFap phenomenon (where men sign up to no porn, no masturbation, no sex for a set period of time) very interesting, both as an attempt to refuse the domination of pornography—sold as individual transgression but damaging to its participants and the social good, more broadly—and as an attempt to reset one’s entire outlook on desire, the opposite sex and life itself.

Stivers writes: “Tolstoy’s understanding of sex—as a form of degradation of one’s partner—would explain a lot about today’s dating world.” Can we be married and abstain from non-procreative sex, not just in that depressed-jokey way about proximity killing desire, but as an active decision not to degrade each other? Even Kant, shining a light on all superstitions, noted that sex involves treated the other as a means to an end, rather than an end in himself. The marriage contract operates as a kind of execption to this rule, where we contract out our genitals for temporary use (romantic, isn’t it), but the fundamental point is that sex often cuts against the esteem we might otherwise have for our spouse. Stivers concludes with beautiful paradox: “it strikes me that the single best way to keep the sex alive in a marriage would be a sincere attempt on both sides to remain abstinent.”

Apart from sex, there is death, and Ashley Frawley wrote for us this week on the horrors of “assisted dying.” Frawley argues that deciding to die with the state’s assistance is not an expression of liberal freedom, but rather the homicidal overreach of bureaucracy itself: “Assisted dying is the quintessential policy of our times. It is a policy that reflects the fatalistic mindset of those who rule over us, leaders who can no longer promise a good life so instead offer a ‘good death.’”

Elsewhere, Hamilton Craig reviews Kyle Edward Williams’ recent Taming the Octopus: The Long Battle for the Soul of the Corporation arguing that the planned economy never really goes away, and that we must always understand who it is that rules over us: “Competition is a temporary interlude through which one set of dominant elites is replaced with another. Once a new elite is in place, its members become rulers. The negotiation of a compact between subject and ruler is the business of politics. In order for this business to begin, we must first know that we are ruled.”

Finally this week, with a great counterpart to Craig’s piece, we have Darel E. Paul on NGOs: “The professional class is peculiarly suited to the non-profit sector, because it is unusually dependent on nonmarket and state-mandated market forms of revenue.” The over-production of college graduates has generated an enormously bloated bureaucracy of the seemingly well-intentioned. This “shadow party” has enormous power, and is naturally extraordinarily interested in keeping the system running in its favor: “True to its class interests, this shadow party isn’t interested in undermining capitalism, but is very interested in racial equality, sexual diversity, immigrant rights, and carbon neutrality. And the way to secure all these goals is to funnel more of the profits of capitalism into the production of professional services—community activists, educators, counselors, immigration lawyers, and policy entrepreneurs.”

Nina Recommends

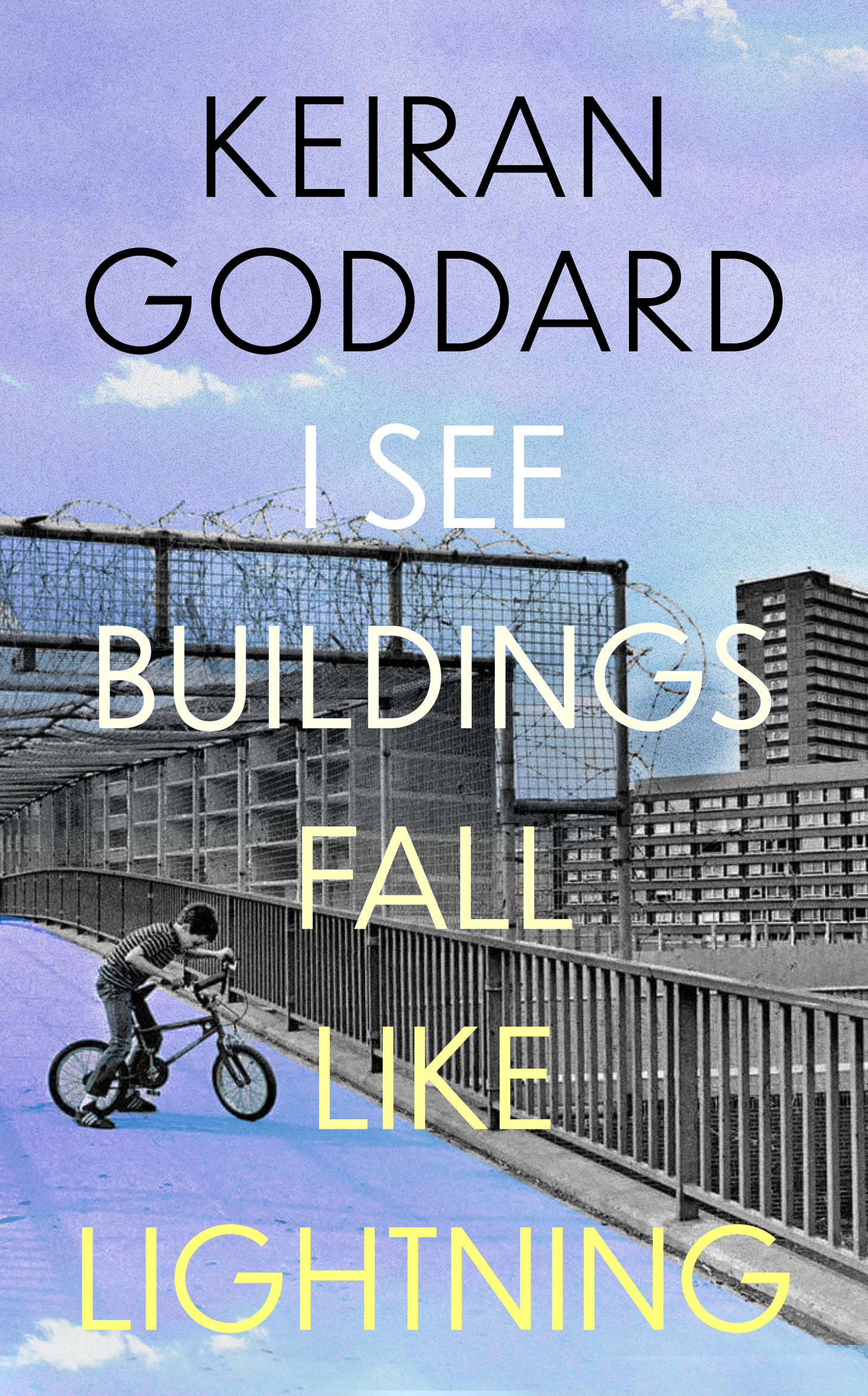

This week I read British writer Keiran Goddard’s second novel, I See Buildings Fall Like Lightning (Abacus) (Bible readers will hear echoes of Luke as well as René Girard in the title). It’s out in the States as an ebook from Europa Editions. Told five-handed by a group of friends who’ve spent their lives in the shadow of a housing estate, we see how at thirty, the group are feeling the weight of possibility (and its absence) heavy upon them.

I See Buildings shares some similarities with Paul Murray’s 2023 The Bee Sting, not least in its polyphonic story-telling and reflections on class. But where Murray’s novel is expansive at six hundred pages, Goddard’s is pithy and epigrammatic. It is, above all, a political novel: the smashing of working class solidarity and the rise of the gig economy (“I don’t really have a boss to get angry at, other than my phone, the green dot on the map and the timer in the corner”). Competing political conceptions of housing—public and private—loom large, and the horror of Grenfell Tower is ever-present, where in London in 2017 more than seventy people died in a tower block fire that raged as a consequence of cheap, flammable, and unregulated cladding.

I See Buildings is a novel about attention, friendship, and love, and of talking honestly in the face of violence, drug use, depression, male suicide and poverty. It avoids didacticism but is unashamedly earnest at the same tine. There are some very funny lines too, most of which are too rude for me to post here. But very funny.

This week I watched Ryszard Bugajski’s 1982 film Interrogation (Przesłuchanie). Censored under communism until 1989, the film depicts Tonia (Krystyna Janda) being arrested after a night out drinking. Her interminable capture and interrogation depict a pathological system adamant that one must confess, precisely because the system demands it. Tonia’s apoliticality, her persistence in relating to others, in never snitching, demonstrates a rare form of resistance, that of the non-political against the incursion of politics into every mode of life. Goddard’s novel shows this too—not just bread, but roses—even if you’re in a cell and all you can grow are grains of wheat moistened with your own spit in the gap between the prison window and the outside, as the women in Interrogation do.

The link for the podcast launch event shows only the location (KGB bar) but not the date or time. Is there any more info available?

Have you ever been to the Tenement Museum chronicling the NYC immigrant experience over time? It's a little heavyhanded ideologically but they have an incredible building down on the Lower East Side.