In a recent Financial Times feature, the literary scholar Orlando Reade traces a phenomenon that has also been of interest to me for over a decade: the influence of René Girard on a growing subset of the American right. The starting point of Reade’s discussion is the conversion experience of sorts that JD Vance experienced at a 2011 speech given by Peter Thiel at Yale Law School. By Vance’s later account, hearing this speech led him to follow Thiel’s path: out of competitive legal career, associated in Thiel’s Girardian account with mindless, sterile imitation, and into the tech world, where contrarian impulses still had some possibility of thriving. As Reade puts it, “it wasn’t the billionaire’s logic that caused this change of heart. It was that of René Girard.”

Although Reade doesn’t make note of it, it’s striking that this scene, ostensibly about rejecting imitation, is a classic illustration of Girard’s thesis that all desire is mediated. Thiel, on that day at Yale Law, became Vance’s mediator, a model for his desire—yet in this case, the way that desire was articulated was itself overtly Girardian. (I suspect the irony wouldn’t have been lost on Girard.) At a later point, Vance also underwent a more literal conversion experience, embracing Christianity—once again, mediated by Girard, via Thiel. As a result, we now have a self-declared Girardian, one degree removed from the thinker himself, next in line for the presidency.

Reade thinks Vance and other conservatives misread Girard. This would be unsurprising to Girard, given the cognitive distortions and self-deceptions that inevitably take hold within the sorts of dynamics of desire, influence, and imitation mapped out above, especially among ambitious arrivistes from the provinces who have made their way from humble beginnings to the very center of worldly power. (As an aside, the notion of Vance as a Julien Sorel who has read Girard somehow recalls the second part of Don Quixote, in which all the characters have read the first part. It seems today’s equivalents of the literary antiheroes analyzed in Deceit, Desire, and the Novel have read Deceit, Desire, and the Novel.) In any case, Reade offers a critique, in what we might call left-Girardian terms, of the coterie of self-declared right-Girardians now in close proximity to power. Their problem, as Reade seems to see it, is that they cherry-pick the parts of Girard’s arguments that can be used against the left, while ignoring all those that might be marshaled against them; they are often blind to their own participation in the same patterns of scapegoating over which they reproach their enemies.

All this seems obviously true. It is also true that Girard isn’t an entirely convenient thinker for right-wing culture warriors: He was difficult to read politically on any clear right-left axis, and tended to eschew public displays of partisanship in favor of what he called “political atheism.” There are plenty of things he said that could be enlisted on behalf of right- or left-wing positions. This is why, if you spend time in Girardian circles, you will find they are more politically diverse than just about any other intellectual scene, truly running the gamut from straightforwardly woke to ultramontane-reactionary.

In the process of critiquing right-Girardianism, Reade also attempts to downplay the centrality of “victim power” to Girard’s analysis of the contemporary world, commenting critically on a piece of my own writing that made the case for that centrality. Reade claims there is just “one moment in I Saw Satan Fall Like Lightning that recent readers”—myself among them—“have fixated upon. Girard mentions that the Christian concern for the victims could be exploited in ways that were deceptive and instrumental.” But these were only “brief and suggestive remarks,” Reade says. Elsewhere, he asserts, Girard “praised this development,” i.e. the “rise of victim power.”

It’s hard for me to see how any careful reader can view Girard’s critique of the dangers of “victim power” as a minor or peripheral element of I See Satan. For instance, in the chapter of the book called “The Twofold Nietzschean Heritage,” Girard writes: “The most powerful anti-Christian movement is the one that takes over and ‘radicalizes’ the concern for victims in order to paganize it. The powers and principalities want to be ‘revolutionary’ now, and they reproach Christianity for not defending victims with enough ardor.” Here, Girard sounds rather close to the right-wing claim that left-wing “victimist” ideology is completely hegemonic. He also compares what he calls the “other totalitarianism” which “does not openly oppose Christianity but outflanks it on its left wing” to the totalitarianism of the Nazis, and concludes that the former is “the most cunning and malicious of the two” and “the one with the greatest future.” I don’t see how Reade’s claim that “victim power” is a minor point for Girard can be sustained in light of such statements.

I imagine Reade takes this untenable position because he is on the left, and making “victim power” central to your story about politics today seems to him like a necessarily right-wing move. (I will explain later why I don’t think it is.) This dimension of Girard’s thought seems to him to subject all claims of “concern for the victim,” along Nietzschean lines, to a hermeneutic of suspicion, casting them as veiled stratagems of power. If you think victim concern is a covert means of pursuing power, Reade seems to conclude, you must be explicitly or implicitly attacking the left, since—as I take it he acknowledges—the left stakes its political project on the defense of victims. And if you argue that this is the main or only way power is pursued today, you must also be claiming that the left is powerful and the right is powerless—in other words, you must buy into the right’s own claims to victim status.

Reade asserts that in my essay on victim power, I “overlook Girard’s praise of victim concern.” It is arguably true that in that particular essay, I didn’t emphasize the fact that Girard believed the rise of victim concern, whatever its excesses, represented an indisputable and irreversible form of social progress. In my defense, I did write, for instance, that “Christianity … dissolves the moral basis of the surrogate victim mechanism, and by doing so makes possible the modern world’s achievements”; I also noted both the rise of empirical science and the judicial system as concrete instances of the modern achievements praised by Girard. But what I assume Reade felt was missing from my account was a clearer indication that Girard would’ve objected to, say, overt cruelty towards refugees and the poor.

It is worth observing here, however, that the chapter of I See Satan in which Girard, as Reade puts it, “praises victim concern” is also a mordant critique of the bien-pensant academic left of the 1990s, which regarded the modern West as the most oppressive society ever to have existed. (I’m referring to chapter 13, “The Modern Concern for Victims.”) As Girard points out, this self-flagellating worldview is itself a symptom of the very civilizational advancement it refuses to acknowledge. He writes: “Never was a society, we often hear, more indifferent to the poor than ours. Yet how could this be, since the idea of social justice, as imperfectly realized as it may be, is found nowhere else?” He goes on: “The global society now in the making is truly unique. Its superiority in every area is so overwhelming, so evident, that it is forbidden, paradoxically, to acknowledge the fact, especially in Europe.” In other words, even Girard’s positive account of victim concern also forms part of his critique of the intellectual pathologies of contemporary left-of-center thought, which seeks to “outflank [Christianity] on its left wing.”

For what it’s worth, I agree with Reade that Vance’s spreading rumors about Haitian migrants in Springfield, Ohio was shameful, especially for someone who claims to be a Girardian, and I said so at the time. However, I also think Reade’s seeming effort to claim Girard as a left-liberal exponent of “victim concern” while impugning conservatives as callously lacking in such concern is in error in two ways. First, it risks falling into a partisan trap that mirrors that of right-wing Girardians, who are only able to see the scapegoating mob when they look at their liberal nemeses. As Girard insisted, seeing your partisan enemy as the perpetrator of scapegoating is always the easy part—the harder part is perceiving that you and your side also perform that role.

Second and more importantly, to view the contemporary Trumpian right—as I take it Reade does—merely as sadistic victimizers, whipping up mobs against the most vulnerable, is to miss the degree to which Girard’s critique of “victim power” always had the potential to cut in both directions politically. I wrote in the “victim power” essay that “the best alibi for scapegoating someone is to accuse them of scapegoating others.” Although my example at the time (late 2022) was (implicitly left-wing) “cancel culture” pillorying its victims for “sins against the victim class,” the description applies to various right-wing causes célèbres of recent times. Why, after all, were we enjoined to be concerned about the Haitians in Springfield? On behalf of the ultimate innocents—helpless house pets!—as well as poor residents who had been priced out or were no longer able to access strained social services. Vance justified his spreading of the tale as a means of standing up for forgotten Americans of whom he claims to be the tribune. The right falls back on the logic of victim power just as the left does—it just picks different victims.

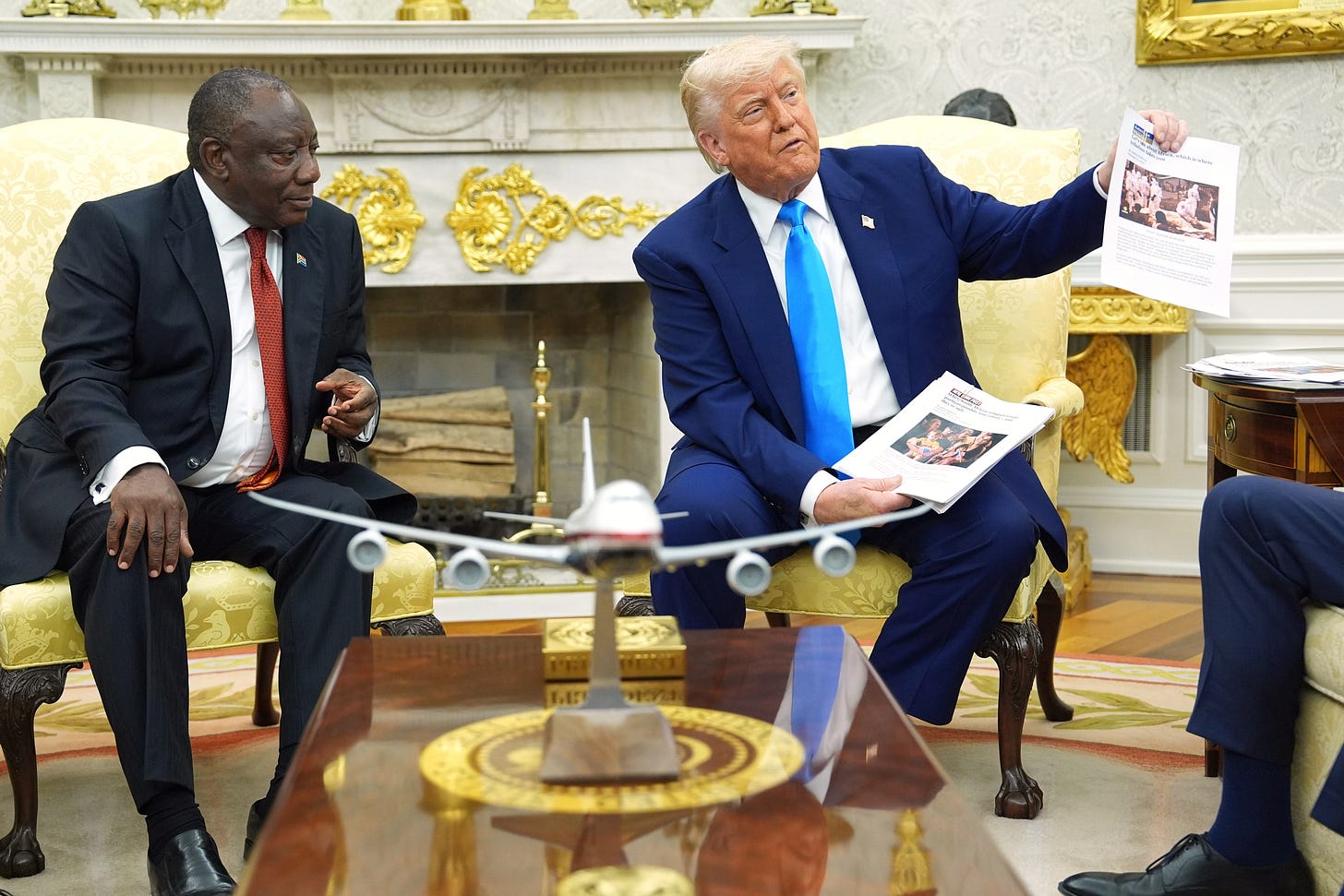

It is important to note here that the most effective strategy the right has seized upon to wield power against its enemies in recent times has been the weaponization of accusations of anti-Semitism, which it has pursued in terms that have often mirrored left-wing identity grievances in nearly every detail. In effect, after the Oct. 7 attacks Jews and Israelis were enlisted by the Republican Party as an anchoring point for its broader ideological crusade against its left-wing enemies. I would read the success of this effort as further evidence for Girard’s claim, which I endorsed in the essay critiqued by Reade, that victim power is the primary logic by which power is now exercised. A more extreme and bizarre illustration is the Trump administration’s championing of the cause of white South Africans, whom right-wingers claim are being subjected to “genocide,” much as progressives have long claimed for various favored victim groups (“trans genocide”).

The irony here is that, if you have followed the far-right fixation on South African (and Rhodesian) whites on social media in recent years, you will recognize its close connection to the neo-Nietzscheanism of figures like Bronze Age Pervert, who follow their philosophical lodestar in rejecting the crypto-Christian logic of victim power. What makes Afrikaners and Rhodesians “based,” for this camp, is that they are nobody’s victims, but a latter-day Männerbund of Aryan adventurers who asserted their claims to land by right of conquest and established themselves as a quasi-aristocracy ruling over a lower-caste majority—until the West forced them to accede to the degenerate modern principle of majority rule. In other words, the importance of Southern African whites to our latter-day Nietzscheans was their status as the surviving avatars of an otherwise lost “master morality,” over and against the “slave morality” that has overtaken the West. It is likely in part this cluster of ideas that led to the Trump White House’s decision to give white South Africans a fast track to refugee status, shaped as its outlook is by the obsessions of very online young staffers. And yet, the Boers arrived on American shores not as conquerors, but as members of that ultimate victim class: the refugee. (On another level, this is no surprise: As anyone who follows the online right subculture can tell you, its members are often some of the most aggressive dramatizers of their own victimhood around.)

Girard argued that the Nazi form of totalitarianism, which had sought to “bury the modern concern for victims under millions and millions of corpses,” and thereby depose Christian-derived “victim morality” and reassert “master morality,” had simply failed. For him, this was evidence that the Judeo-Christian revolution in values was irreversible, revealing nothing less than the working out of the divine plan. It is precisely for this reason that he argues the “other totalitarianism”—the one which radicalizes victim morality rather than discarding it—is the more dangerous one today; even our would-be Nietzscheans can’t help but succumb to its logic. I think this, more than a particular antipathy to the left, was why Girard envisioned the antichrist as “a super-victimary machine that will keep on sacrificing in the name of the victim”: because the “powers and principalities,” whatever form they might take, can no longer help but fall back on the inexorable logic of victim power.

Reade seems unsure what to make of the fact that members of a political faction that often seems to revel in its unconcern for the vulnerable has prominent members who take Girard as their mentor. But Girard was clear that the revelation of the victim mechanism would not save us from our continued participation in that mechanism’s dynamics; on the contrary, he emphasized that its discovery was the source of new forms of error and strife. As he wrote: “If we gain great advantages from our liberation from scapegoats and sacrificial rituals, this freedom is also the occasion of oppression and countless persecutions. It is a source of peril and the danger of destruction.” He also insisted throughout his body of work that in moments of heightened polarization, we must attend not to the differences between the antagonists, but their similarities. The fact that our major political factions both stake their claims to power and legitimacy on the defense of victims is just the latest proof of the enduring value of this approach.

This week in Compact

R.R. Reno on Catholic social teaching and its prospects under Pope Leo XVI

Gord Magill on a common-sense trucking reform

Thomas Gallagher on the outcome of the Romanian election

Grant Martsolf and Brad Wilcox on AI’s threat to working-class families

Pelle Dragsted and William Banks on Nordic lessons on “abundance”

Steven Watts on Disney’s decline

Stephen Adubato on the “enrollment cliff” facing universities

Thanks for reading!