The First Tech Right

Why the 1990s effort to align Silicon Valley with the GOP failed

The term “tech right” seems to have been coined by Richard Hanania in a 2023 Substack post that heralded the rightward turn of various Silicon Valley luminaries, most prominently PayPal mafiosi Elon Musk and David Sacks and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, all of whom would go onto form close alliances with Donald Trump and throw their support behind his 2024 campaign. To many observers, the who’s who of tech CEOs at Trump’s second inauguration was the culmination of a shocking development: the rightward shift of a sector of the US economy that had been closely aligned with progressive causes and the Democratic Party for decades. Since the turn of the millennium, Silicon Valley had donated to Democrats, to the tune of 70 to 80 percent, as compared to other major industries like banking and finance, which were either GOP-dominated or evenly split.

Some have sought the philosophical origins of the tech right in earlier eras of “reactionary modernism”—the historian Jeffrey Herf’s term for a school of thought that was technologically accelerationist but socially conservative, which was concentrated heavily in interwar Germany and Italy. Despite the unsavory political affiliations of many of the reactionary modernists, Andreessen himself has encouraged this association, invoking some of these precursors in his 2023 “Techno-Optimist Manifesto.”

However, the tech right has much more immediate precursors. In the initial Silicon Valley boom of the 1990s, the burgeoning industry’s political leanings were not yet entirely evident. Many found the simultaneously culturally libertine and economically libertarian spirit of the Valley difficult to make sense of at a time when free-marketeers were overwhelmingly allied with the religious right—forming two legs of the fusionist stool—and most onetime hippies had presumably grown up to be Democrats, like the Clintons. One major attempt to make sense of the perplexing tech sensibility was Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron’s analysis of “The Californian Ideology.” They characterized the worldview in question as a fusion of “the free-wheeling spirit of the hippies and the entrepreneurial zeal of the yuppies.”

Perhaps the quintessential embodiment of the Californian Ideology was the writer and activist John Perry Barlow, whose career brought together the 1960s counterculture, the Republican Party, and early digital technology. In his youth, Barlow was a disciple of LSD guru Timothy Leary. He later went on to collaborate closely with the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir, penning several of the band’s most famous songs. But by the Reagan Era, he had returned to his native Wyoming, where, in addition to maintaining the family ranch, he ended up working for Dick Cheney’s first congressional campaign—even as he continued to keep up with his fellow Deadheads on early internet forums.

Barlow is a main character in Fred Turner’s From Counterculture to Cyberculture, which documents how and why back-to-the-land hippies became early adopters of cyberspace via a “New Communalist” philosophy that emphasized spontaneity, decentralization, and horizontal networks. The early prophets of cyberculture linked these ideals rhetorically to the history of the American frontier (as in the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the digital rights organization co-founded by Barlow in 1990). As Barbrook and Cameron detail at length, what emerged out of this was a neo-Jeffersonian political vision of localism, property rights, small government, and free association.

This outlook created an opportunity for an alliance with the Republican Party, newly empowered and radicalized by its sweep of Congress in 1994 under House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s leadership. Gingrich, as it happened, was a longtime disciple and friend of the popular futurist Alvin Toffler, whose celebrations of information technology were unsurprisingly well-received in Silicon Valley. Gingrich claimed that his Contract with America—the Project 2025 of the era—was inspired by Toffler, and wrote a foreword to Toffler’s 1995 book Creating a New Civilization, which he assigned as homework to his congressional delegation.

Toffler had long claimed that what he called the Third Wave—elsewhere described as the rise of an information or knowledge society—would bring about the obsolescence of the centralized state bureaucracies of the 20th century and the mass institutions associated with them. The era of big government was over, by this account, not simply because midcentury liberalism had failed, but because of the working out of a larger technological logic. When Gingrich explained his signature projects of shrinking the federal government, devolving power to state and local authorities, reforming education, and deregulating industries, he frequently cited Toffler’s analyses.

Much like the tech-MAGA alliance of 2024, Gingrich thus sought to place the Republican Party at the vanguard of historical progress while positioning Democrats as the last-ditch defenders of moribund institutions. Democrats under Clinton, of course, had a pro-tech faction represented by the Atari Democrats and Al Gore. But in the mid-’90s, it wasn’t at all implausible for Gingrich to imagine that the more natural alliance was between Silicon Valley and the GOP, since both grasped that the Third Wave meant the end of top-down institutional control and a proliferation of horizontal networks.

Two summits held in 1994 and 1995 aimed to consolidate this alliance. Oriented around the theme of “Cyberspace and the American Dream,” these gatherings sought to forge a new coalition of cyber-intellectuals like Barlow with tech industry leaders and GOP politicians. The convenor of these events was George Gilder, like Toffler an influential conservative futurist as well as a Republican operative and a contributor to Wired magazine—the Pravda of the Californian Ideology. The first summit resulted in a “Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age,” co-written by Gilder, Toffler, and Wired contributor Esther Dyson. Drawing heavily on Toffler’s “Third Wave” concept, the “Magna Carta” outlined a political vision that informed Gingrich and his fellow Republicans as they pursued the deregulation of telecommunications the following year.

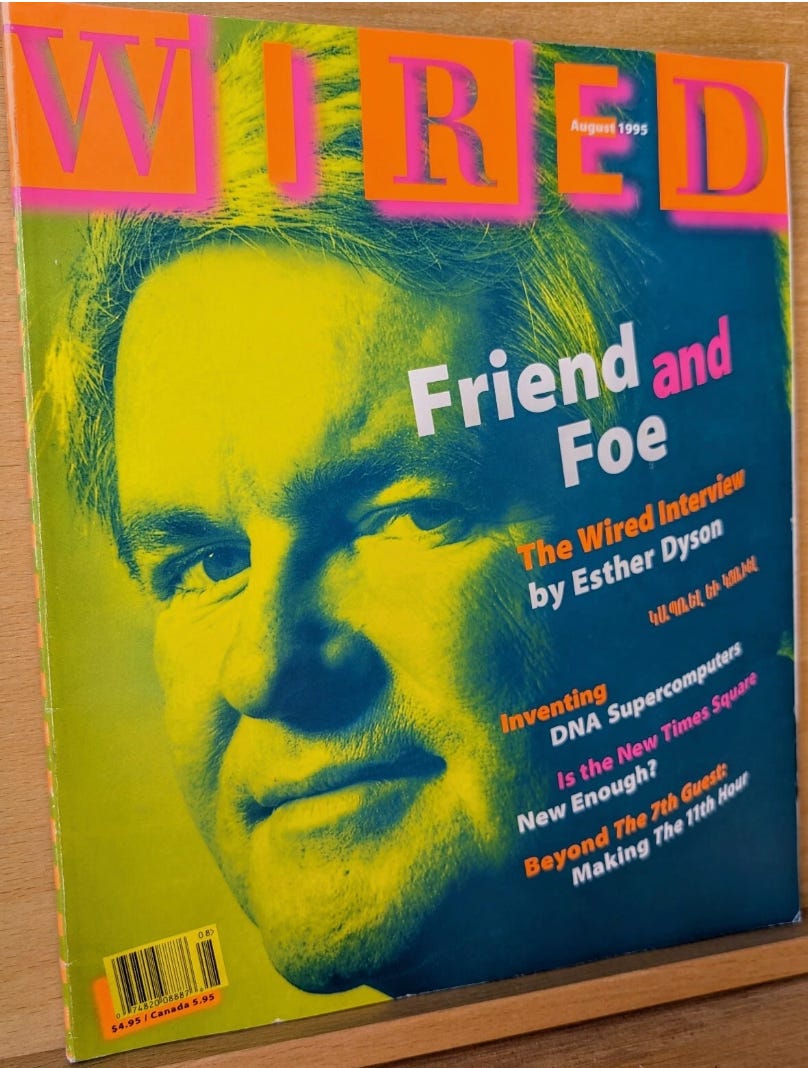

The “Magna Carta” was the most impactful intellectual output of the nascent alliance between Silicon Valley and Republican Washington. The Telecommunications Act drafted by Congress in 1995 and passed in 1996 reflected its basic idea that, in Turner’s words, “communications technologies and the Internet [were] models of open markets and an open political sphere and at the same time … tools to bring them about.” The follow-up summit, held in Aspen in August of 1995, saw more friction between the disparate participants. But it also coincided with another landmark moment in the short-lived ’90s tech-GOP symbiosis: Dyson’s lengthy Wired interview with Gingrich, which lays out their differences as well as their many convergences.

The Wired cover featuring Gingrich calls him “Friend and Foe.” It’s clear from the interview that the main area in which they are “foes” is on what was then called “traditional family values.” Dyson and the rest of the Wired crowd may have been favorable to deregulation and hostile to bureaucracy, but they derived their social values from Summer of Love Haight-Ashbury (the basic synthesis described by Barbrook and Cameron). They also detested censorship, which the Republican Party (along with parts of the Democratic Party) supported in its various efforts to “legislate morality.”

That gets us to the reasons the tech right 1.0 failed to endure as a coalition. As the ’90s wore on, the GOP leaned more and more into moralizing crusades, culminating in the impeachment of Bill Clinton, that could only alienate potential allies like Dyson. Meanwhile, the Third Way Democrats “triangulated” enough to erode the GOP’s advantages on deregulation and decentralization while showing that they could combine an embrace of these values with a laissez-faire morality more amenable to Silicon Valley.

The emergence of the tech right 2.0 nearly three decades later was a sign of approximately the opposite development. The religious right put Dyson off about the GOP in the Clinton era, but by the early 2020s a Republican libertine-in-chief had brought religious conservatives to heel. By the early 2020s, the Republican position on sexual morality had drifted closer to that of the 1990s Democrats. The tent was big enough that GOP militants could come to the defense of transhumanist serial adulterers like Elon Musk.

The Wired set shared with Gingrich’s GOP the conviction that the breakdown of big bureaucracies would enable the flowering of Burkean “little platoons.” As Gingrich put it to Dyson: “I really like the Tocquevillian model—the sense that you have lean government and big culture. The culture pounds away at the idea of civic responsibility, doing your duty, being an active local leader, being engaged in acts of charity.” The actual history of network technologies in the intervening decades makes this seem like a delusional fantasy. New technologies have eroded the authority of big government bureaucracies, but have helped do the same for the local, organic forms of authority fetishized in the Contract with America. (This was already underway by the time the GOP took Congress: Robert Putnam published his first essay version of “Bowling Alone” in 1995, the same year Gingrich was interviewed by Wired.)

The second iteration of the tech right is succeeding where the first failed in part because the transformation heralded by Toffler has not led to a flourishing of Toquevillian civil society. Instead, we have seen the supplanting of mass organizations by a new logic of centralization: the brutal, winner-take-all monopolism exploited in different ways by Donald Trump and the titans of Big Tech. Trump’s hostile takeover of the GOP capitalized on the erosion of the mediating layers of conservative politics just as the forms of “connection” promoted by tech platforms thrive amid increasing disintermediation and disorganization. For the tech right to rise, in other words, the “New Communalist”-Burkean synthesis that was its original rationale had to die.

This week in Compact

Heather Penatzer on the errors of BRICS

Emmett Rensin on the false conflation of conspiratorial thinking with mental instability

Eli Sennesh on an upcoming bill funding scientific agencies

Juan David Rojas makes a left-wing case for lowering taxes

Carlos Dengler on the deceptiveness of liberals’ performative guilt

Philip Cunliffe on how Trump challenged the EU

Ashley Frawley on the eugenic horseshoe between Sydney Sweeney and the trans lobby

Edward Luttwak reviews a biography of Curzio Malaparte

I think the big development in tech is simply that California became a dysfunctional one party Democratic state and ran itself into the ground.

Yes, woke and tech anti-trust on the Dem side are big issues, but literally not being able to buy a house and having to avoid homeless junkies in the street is radicalizing. And while COVID will eventually fade from memory the stark red/blue contrast on that burns bright right now.

You can see an attempt to address this with "abundance", but if California couldn't embrace abundance when elections were still competitive I think its going to have a really hard time breaking "the groups" when they have a total electoral lock.

The Curse of WIRED: Beware of getting on the cover. It’s a sure sign that your fortunes are about to take a downward turn.