The Long Birth Pangs of Post-Postmodernity

How my literary theory grad seminars predicted the Trump Shock

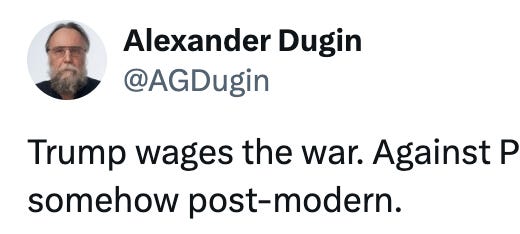

My candidate for tweet of the week comes from Putin’s (alleged) Rasputin:

Dugin posted this on April 9, the day the “yippy” bond market prompted President Trump to pause most of his “Liberation Day” reciprocal tariffs (with China the big exception). Whether the Russian philosopher intended it this way or not, I think we can be quite precise about what he’s getting at, with some help from Stuart Jeffries’s 2021 book Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern. Jeffries identifies the origin of postmodernity/postmodernism with a specific presidential act: Nixon’s 1971 decision to end the gold standard and allow the value of the US dollar to float freely, which liquidated the economic order created nearly three decades earlier at Bretton Woods.

As Jeffries explains, with reference to Nixon’s decisive meeting with top economic advisors and officials:

The arguments at Camp David were the economic equivalent to contemporary arguments in literature and philosophy departments. Those who sought the end of the gold standard envisaged an end to financial regulation. This was parallel to what Michel Foucault sought when he called for literature to be liberated from the constraint of authorial control in favour of the free composition, decomposition, recomposition and manipulation of texts. The Nixon Shock helped produce the world we live in—one of deregulation, free-floating signifiers and no less free-floating capital.

Nixon made his decision out of immediate necessity. The expenses of the Vietnam War were draining the treasury, and un-pegging the dollar from gold gave the government more leeway to print money to pay the bills that were coming due. More greenbacks were already in circulation than the vaults at Fort Knox could redeem, which was already occasioning panicked runs on the dollar in foreign exchange markets. But Jeffries’s account suggests that decoupling value from precious metals and allowing it to circulate freely also realized a deeper cultural logic that was already in evidence much earlier—for instance, in Ferdinand de Saussure’s seminal 1916 Course in General Linguistics, which introduced the model on which all postmodern theory was founded, in which words and other forms of symbolic communication circulated in the absence of any necessary relation to referents in the world, achieving meaning only differentially and relationally (like currencies in the post-Bretton Woods world).

An array of commentators, notably former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, have drawn the parallel between the Nixon Shock and Trump’s ongoing effort to restructure the global economic order. The more articulate figures in Trump’s orbit, notably Chair of the Council of Economic Advisors Stephen Miran, have pointed in a similar direction. But as Ross Douthat noted last week, before this week’s tariff pause, the “‘Nixon shock’ was forced upon his presidency to a degree that this shock is not being forced on Trump.” What befuddled and distressed many observers of the past week and half’s turmoil, even many who are otherwise sympathetic to the goal of reshoring industry and reducing US dependence on foreign manufacturers, was what seems like the willfulness and caprice of Trump’s approach.

If most tend to see Trump’s move as an unforced error, the president himself seems to think of it differently. In recent days, after he escalated his punitive tariffs on China to 145 percent, a viral video recorded during the far less consequential trade war of his first term has been circulating once again. “I am the chosen one,” Trump declared, glancing up at the sky. “Somebody had to do it. So I’m taking on China.” (His sense of himself as a man of destiny seems to have been strengthened by his survival of two assassination attempts last year.) What’s strange about seeing the video now is that it was recorded in 2019, before the fallout of the pandemic revealed the brittleness of the system of global trade erected over the past five decades as well as America’s inability to manufacture essential goods—a reality made even more clear by the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, which laid bare the decrepit state of our defense-industrial base. It is hard to dispute that Trump, whatever the flaws in his execution then and now, was prescient in recognizing the limits—and the losers—of the economic order inaugurated by Nixon.

This brings us back to Dugin’s dictum. When I was in graduate school in the late 2000s and early 2010s, most everyone accepted that “postmodernism”—the collection of ideas that had prevailed in the humanities since the years after the Nixon Shock—had grown stale, and a new paradigm was needed. Many of us thought, especially in the wake of the financial crisis, that a new iteration of Marxism was what the time demanded. All in all, we saw something like that emerge more in the nascent realm of left-populist politics of the time than in the academy, where ever more abstruse forms of identitarianism continued to proliferate. None of us expected that the most foundation-shaking contestation of the postmodern paradigm would come from an entirely different realm: the antics of Donald Trump (an impeccably postmodern figure). As the Trump Shock reverberated this week and we tried to assess the fallout, I was reminded of nothing so much as my graduate seminars of over a decade ago, in which we groped around trying—and mostly failing—to find a theory adequate to the reality coming into view.

Trump’s defenders will tell us that there is nothing new to discern—their man is simply RETVRNing us to the prosperity of earlier American dispensations, whether the Bretton Woods high point of Fordism or, as has often been suggested during the current iteration of Trumpism, the age of William McKinley. But what these seemingly more solidly grounded eras had in common was the gold standard. Some are claiming that the ultimate aim of Trump’s seeming attempt to undermine dollar hegemony is a restoration of gold as the ultimate arbiter of value, an idea proposed in Project 2025. What is more likely, though, is that we are witnessing yet again the situation famously described by Marx in the opening lines of the Eighteenth Brumaire:

Just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language … In like manner, the beginner who has learned a new language always translates it back into his mother tongue, but he assimilates the spirit of the new language and expresses himself freely in it only when he moves in it without recalling the old and when he forgets his native tongue.

This week in Compact

We’ve published two essential, must-read analyses of Liberation Day and its fallout: David Singh Grewal’s “Liberation Now?” and Christopher Caldwell’s “Does Trump Want to Destroy the Global Economy?” I promise you won’t read anything more illuminating on the subject. Beyond that, our usual variety of coverage:

Julia Yost on the third season of White Lotus.

Garrett Ramirez on the origins of DEI in Obama-Citigroup nexus.

David Moulton on the continued relevance of Paul Ricoeur.

Arjun Byju on the MAHA influencer Casey Means.

Darel Paul on how politics are worsening the baby bust.

Antonio de Loera-Brust on why we must defend the National Parks.

Thanks for reading!

Good piece but I don’t think it is correct that Trump was not forced to act. A) Democrats tried to jail and kill him and by extension all

political opposition and their plan to consolidate control would merely be on pause without action B) The US taxpayer through the Treasury was underwriting socialism in Europe C) The Triffin Dilemma. Similarly, Saussure was wrong about language. For example, thought occurs without it. What we are seeing is that the contradictions in PostModernism finally caught up with it.

"Nixon’s 1971 decision to end the gold standard and allow the value of the US dollar to float freely"

Funny, the right-wing Austrian econ folks didn't like that either. "Either" to the degree Jeffries thinks this was a bad move.

Found an hour and a half long preview of the book on YouTube. Listening now.