The Return of the Assassin

The shifting logic of spectacular violence

I used to reflect often on the disappearance of the figure of the assassin from American public life. After two centuries in which they played a symbolically central role in US history, assassins had been replaced, it seemed to me, by mass shooters around the turn of the millennium. It was as if our culture only had room for one major variety of spectacular, media-oriented violence. Perhaps, I thought, it was no coincidence that assassinations gave way to mass shootings around the time the 24-hour cable news cycle and the internet ended the high era of network television. The scattering of attention across proliferating channels and media seemed congruent with the centrifugal violence of mass shootings, in which both bullets and incidents fanned outward.

Now the assassin is back, so my thesis needs revising. Tyler Robinson, who has just been arrested for the murder of Charlie Kirk in Utah on Wednesday, follows in the footsteps of Thomas Matthew Crooks and Luigi Mangione. Of course, mass shooters are still at it too. Within an hour of when Robinson allegedly shot Kirk, just one state over, Desmond Holly shot himself after injuring two classmates at his Denver high school.

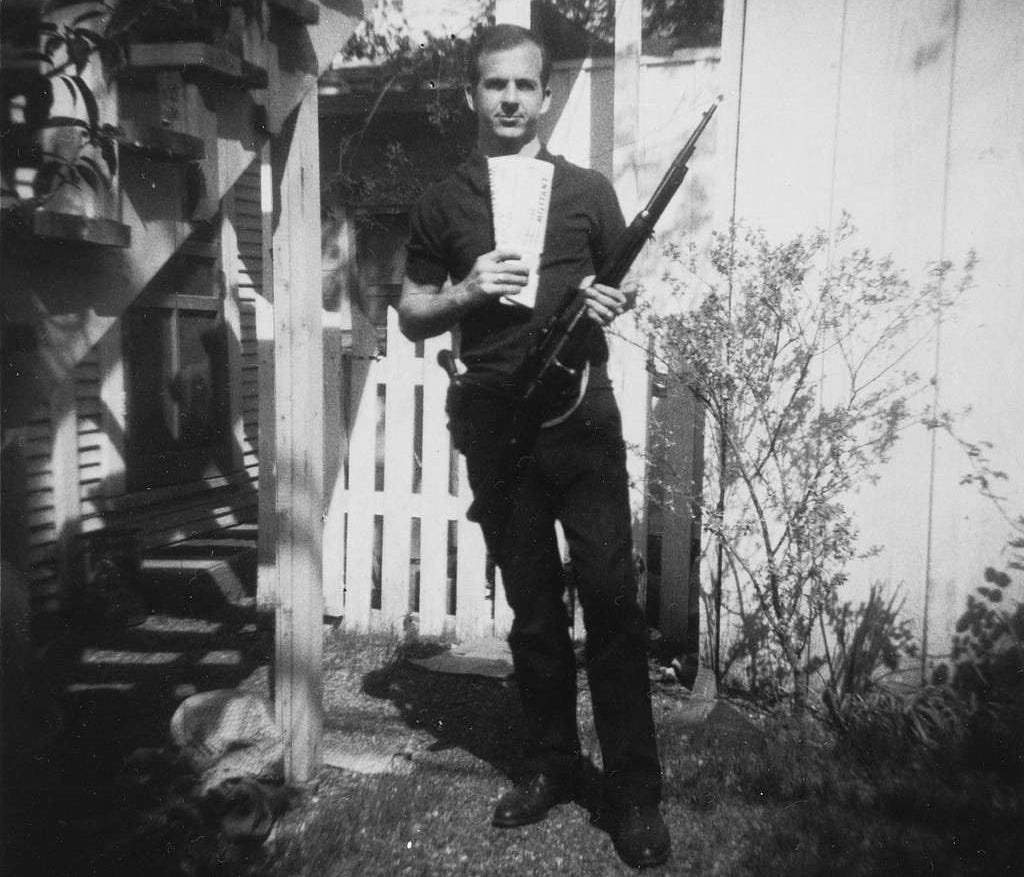

The assassins of the mid- to late 20th century and the mass shooters of the early 21st share many characteristics. They are typically Dostoevskyan “underground men” of some sort: alienated, disaffected nihilists characterized not by their neat representation of some major ideological tendency but their inability to be part of much of anything. Lee Harvey Oswald was a communist, to be sure, but apparently too weird of one to fit in in the Soviet utopia. Sirhan Sirhan claimed that the plight of his fellow Palestinians had driven him to kill RFK, but rather than shipping off to a PLO training camp, Sirhan had joined the Ancient Mystical Order of the Rosy Cross. Mangione has been claimed by many on the online left, but his back history actually suggested he was some sort of Reddit/IDW rationalist.

Over the course of the 2010s, it became typical for liberals to claim not only that the right was to blame for mass shootings because of its rejection of gun control, but that all mass shooters were white men motivated by right-wing ideology (in reality, mass shooters are overall pretty representative of the racial makeup of America) or, in the more sophisticated version, that mass shootings were somehow a manifestation of “white supremacy.” Now that the right has achieved a sort of cultural hegemony, we are hearing a similar refrain that “the left” is broadly responsible for all political violence. The tendency to claim that a spectacular, mediatized act of violence somehow manifests the culture of your political enemies isn’t new. In my experience a lot of liberals somehow blame the ambient Bircher-ism of Dallas for JFK’s assassination, and don’t know that Oswald was an outspoken communist.

The tendency to partisan point-scoring is perhaps the primary obstacle to achieving any insight into the phenomenon in question. Perpetrators of highly public violent acts have laid claim to just about every ideology you can think of, and in many cases, no discernible one at all. What they all have in common is being drawn to committing spectacular acts of violence. This makes them outliers vis-à-vis the population as a whole, so we should expect them in other respects also not to resemble the average political partisan; again, what tends to stand out about them ideologically is their lack of clear belonging to any broader tendencies. To the extent they gravitate toward ideologies, it usually looks like an attempt to find a rationale that might guide and make sense of the impulse toward violence, not the other way around.

When I was theorizing the decline of assassinations and the rise of mass shootings, my question was: Why did individuals of the personality type who might have become assassins start becoming mass shooters in the late 1990s? One theory would be that security for prominent public figures got more effective, and there’s probably something to this, even if recent events call it into question. Another, already stated, is that the shifts in media technology altered the dynamics of public attention and thus the incentives for those inclined to seek attention through acts of violence. On one hand, the logic of violence shifted away from culturally central figures. On the other hand, perhaps the escalating competitiveness of the attention economy increased the rewards for shocking depravity, leading inexorably to Adam Lanza.

My other speculative theory about the shift from political assassinations to mass shootings was Foucauldian. The cultural prevalence of political assassinations seemed to reflect the older structure of sovereignty, in which power was vested in the singular figure of the head of state. It followed that the obvious target of political violence would be the body of the sovereign. Assassins like John Wilkes Booth, Leon Czolgocz, Lee Harvey Oswald, and John Hinckley, Jr. were spiritual descendants of the regicide Damiens, whose dismemberment after his attempt on the life of Louis XV is narrated at the beginning of Discipline and Punish. Within the logic of sovereignty, the default way to go up against power was to “shoot up,” so to speak, at the figure at the pinnacle of its topology. The same logic could also apply to cultural eminences like Martin Luther King (note the name) and John Lennon.

The shift in political violence away from high-profile assassination and toward mass shootings, it seemed to me, recalled Foucault’s account of the shifting landscape of power. The topology of power in the regime of sovereignty was vertical and centralized, but in the “disciplinary” regime that succeeded it, power became diffuse, distributed, and unlocalizable. By the late 20th century, the sort of all-American berserkers who had once sought to decapitate the sovereign seemed to intuit this horizontal, pervasive dispersal of power. Their targets weren’t their superiors, but their peers; the sites of their violent acts were most often that crucial disciplinary apparatus, the school. (To be clear, my theory wasn’t that mass shooters had read Foucault, but that they intuited the same broad developments he described.)

Given that school shootings and mass shootings continue to happen, this logic hasn’t subsided. But if assassinations are back, perhaps that’s because the older logic of sovereignty is too. And indeed, it is. Of course, the most prominent victim of (attempted) assassination is Donald Trump, who openly muses about kingship. In seeking to dismantle the complex, decentralized structures that characterized power in the neoliberal era, Trump has reinserted the sovereign decision into the center of our politics. The return of the assassin seems to respond in part to that haphazard re-centralization. (Charlie Kirk, it’s worth noting, was characterized as a sort of MAGA dauphin.)

The high-profile assassination and assassination attempts that occurred regularly between 1963 and the early ‘80s were symptomatic of the crisis and decline of the midcentury American political order. That high era of assassinations came to an end just as the age of neoliberal globalism came into its own. The assassin’s return offers another clear indication that we are lurching into another such transition. The End of History, characterized by a form of power that seemed unassailable precisely because it was unlocalizable, also gave rise to the horrifying ritual of the mass shooting, a sort of public violence that was as strangely apolitical as power sought to be. This ritual now coexists with a reversion to the one that preceded it, offering a particularly grim indication of the schizoid regime under which we’re living.

This week in Compact

Joel Kotkin on the false promise of immigration as an economic panacea

Helen Andrews on China’s gaokao exam

Adam Kirsch on why tyrants love transhumanism

David Cowan on Nvidia

Heather Penatzer on the dangers of privatized national security

Assassins like Luigi and now Tyler Robinson have received far more media attention (and adulation) than any individual mass shooter since Columbine.

Meanwhile, mass shootings have become everyday, almost banal events, and the media scrupulously avoids showing the faces of the shooters themselves.

This would seem to create an incentive structure that will encourage disaffected loners to become assassins.

Small edit: should be Czolgosz (if I have it right)