Last weekend, New York was host to a “Hegelian e-girl summit.” According to the group’s “Mini-Manifesto,” bourgeois democracy has fostered a “culture of immediacy” that banks on an artificial, dialectical “ping-ponging” between “liberal and fascist excesses.” As an antidote, the e-girls propose to “restore a culture of genuine mediated intelligence” and to resist “the familiar logic of abstract opposition, friend and enemy, to which we have become accustomed.” What exactly that would look like remains unclear.

In any case, their summit was well attended, Compact summer intern Lily Zuckerman tells me. The people she spoke to “mostly knew very little about Hegel.” When asked what the point of the party was, they gave mixed answers. “Some were equally as mystified as I was and some responded with a little hostility, understanding the aim of the event to be just getting together and talking.” After several hours, the hostesses addressed the crowd regarding “the need for a vibe shift and the memetic power of e-girls: ‘We are not only people, we are concepts…standing against this present so that we can present this present to itself.’” Their speeches were “calls to action,” albeit “very unclear” ones.

This week in Compact

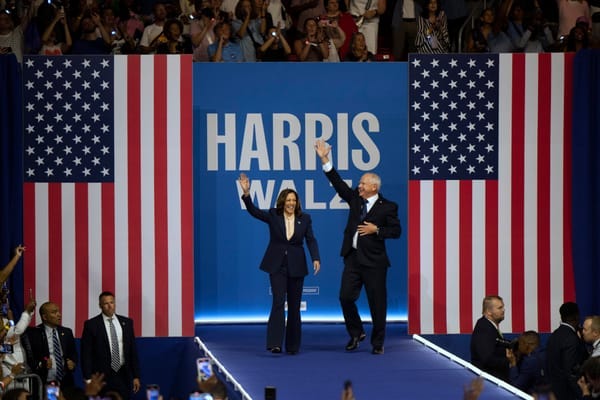

Tim Walz “can’t be framed as a neoliberal Democrat in the Clinton-Obama mold,” Sohrab Ahmari writes. His populist track record poses a palpable challenge to the Trump-Vance ticket, requiring “Team Trump to lean away from both online culture-warring and conventional GOP messaging—and lean into a positive, bread-and-butter populism.”

And though Ryan Zickgraf acknowledges that Walz won’t be “in a position to set the agenda should the Democrats win in November” (as FDR’s VP John Nance Garner once said, the office of VP “is not worth a bucket of warm spit”), that fact that Harris didn’t pick “a safe choice who would moderate the party’s image” represents a “momentary break with the party’s conventional wisdom is worth celebrating.”

Alexander Nazaryan covers the loss of Missouri congresswoman Cori Bush in the Democratic primary, attributing it to her “catering to her brand more than to her constituents.” He compares her abandonment of bread-and-butter progressive policy wins with the way DeSantis turned his focus from successful pragmatic governance to wars on the wokeness of Disney. (Sohrab Ahmari warns Trump not to fall into the DeSantis trap newsletter this week) and to the progressivism of “The Squad.” Nazaryan highlights former Missouri representative

Despite being a proudly nationalistic people, Jamaicans, writes Kingston-native Alexander Causwell, “certainly do not claim” Harris, whose father was born on the island nation. “It is too obvious to too many that she is merely a vessel for whatever the Democratic Party’s current priorities happen to be—a deficiency Donald Harris’s compatriots in Jamaica haven’t failed to notice.”

Catherine Liu writes that “the 21st century Democratic Party is the party of postmodern politics.” Harris’s campaign and her policy positions (or lack thereof) “mime the emptiness of playful signifiers freed from a referential world, indulging in decorative gestures.” Echoing the theories of Jean Baudrillard, she insisted that “within the floating world of simulacral liberalism, they play a game of ‘progressiveness,” without having any regard for the concrete needs of workers or the oppressed.

Darel E. Paul writes that the reason riots are taking place in the UK and in other Anglosphere countries with influxes of migrants is that “the British are more rooted to place” and “much of Britain is poor.” He calls for—in addition to more restrictive immigration policies—greater efforts to foster economic growth. And in his Compact debut, David Goodhart challenges the “two-tier” approach to policing, which seems to hold a double standard for violent “far-right” rioters compared to those rioting for identitarian causes.

Last week, I commented on the vapid, seemingly algorithmically-generated fodder surrounding the opening ceremony at the Olympics. Ashley Frawley took this opportunity to draw attention to the fading role of public intellectuals, and the so-called “experts” and “online contrarians” that have come to take their place. “Society moves forward when we engage in conversations with each other,” which public intellectuals aim to foster. But “it stops,” she warns, “when we shut down our critical faculties and defer to the secularized priestly class.”

And be sure to check out the Compact editors’ commentary on Walz, the riots, and RFK Jr.’s Central Park bear controversy on the podcast.

When in [Turin]…

The Hegelian e-girl summit has inspired some X-users to call for a similar gathering of Nietzschean e-boys. Though I’m neither a Nietzschean nor an e-boy, I must confess to having had a bit of a “fanboy” moment while in Turin, Italy yesterday upon visiting the apartment in which Nietzsche wrote Ecce Homo.

Earlier in the week, Ashley Frawley’s piece—which I read while seated at an outdoor cafe in one of the city’s many picturesque piazzas—made me think back to Pasolini, who I cited in the newsletter a few weeks ago. I also thought of Giovanni Testori, a contemporary of Pasolini who in a discussion with Monsignor Luigi Giussani warned of the growth of “impersonal” global entities “without a physiognomy” that operate at a distance from “place, from concreteness.” Testori continues,

even in the great powers, power always coincides less with the face of the one who nominally holds it: the face of Carter, the face of Brezhnev. It is no longer like it was some ten years ago. You could still see Kennedy; you could still see Stalin. They were what they were, but they still had their faces.

Today we proceed to powers that no longer have physical faces, faces in which the memory of man can recognize itself, however distorted or disfigured. Having wanted to take away…the presence, the seal, the imprint of the Father—the political powers have also become machines— monstrosities, abstractions.

Pasolini and Testori’s warnings turn out to be hauntingly true. In Italy, identitarian diversity rhetoric and “therapy-speak” are now widespread. The youth culture continues to be pervaded by that of the United States. The food culture, whose sacredness reaches quasi-sacramental levels, is being diluted by fast food joints and artificial ingredients. Even America’s puritanical stigmatization of cigarette smoking is starting to gain traction.

On the bright side, Italy’s strong cultural legacy has managed to resist being completely washed away by the waves of the expanding global monoculture. Take the historic architecture and gorgeous churches, which are protected by policies and are revered by the public.

Personally, I was relieved to see that the American tendency to blast air conditioning has yet to make its way over, nor its enshrining of “customer service.” I’m always shocked that the friendliness of waiters is motivated not by tips, but by their genuine congeniality. Unlike in the United States, their kindness comes off not as forced or artificial, but as spontaneous and organic. Sure, they’re not exactly quick to get around to taking your order, and they might cut out for a minute (or 10) for a smoke break. But there’s something about their demeanor that puts you more at ease than the efficient, overly-accommodating American waiter, who seethes with resentment after you send your dish back to the kitchen.

It all makes you wonder why there are less occurrences of depression, suicide, and mass shootings here…

I've spent a lot of time in that square in Turin. There's a wonderful book published by Adelphi called "Lettere da Torino" that collects all of Nieztche's letters he wrote from that apartment. It's in Italian and I don't think an English version exists, although there are some translations online. If you're still in Turin you could probably find a copy from one of the booksellers on Via Po...