Over the past week, there’s been talk of the historic proportions of Vice President Kamala Harris’s possible election into office. Surely, her status as a woman of color doesn’t automatically guarantee that she will advocate for the needs of black Americans (nor for Jamaican- or Indian-Americans), nor that she will receive universal support from them.

Though she has indeed received considerable support from black voters, polls indicate that said support is significantly lower than that of former president Obama. Despite attempts to play up her identification with her fellow black Americans, she’s been called out for “pandering” to them in a manner that one writer felt was “cringe as hell.” Others have gone as far as expressing that she does not deserve black people’s trust—in part for supporting harsh enforcement of marijuana-possession laws which have disproportionately impacted inner-city black men.

This dilemma of Harris’s identity sheds light on two major pitfalls within identitarian discourse: it tends to overemphasize the weight that categories like race and sexual orientation hold and downplays that of more concrete ones like socioeconomic class; and it too often speaks of identity as if it were a flat, abstract reality that belongs to individuals who exist in a vacuum, as opposed to being born organically from a dynamic matrix of relationships, through which traditions, beliefs, and cultural expression are transmitted.

Ever since Hulu started streaming a slew of old HBO shows on its platform a few months ago, I’ve had numerous (younger) friends tell me that they were shocked to learn from The Sopranos that Italian-Americans don’t totally fit into the “white” identity box. As one zoomer said, “I never realized that you guys have your own culture.” While of course, I benefit from “white privilege” to the extent that I (rarely) have to worry about facing discrimination based on the color of my skin (a kid in high school once called me a slur reserved for hispanics), I don’t relate to the culture of those whom Italians would call merigans.

Space for cultural categories like “Mediterranean,” “Maghrebi,” “Indo-Caribbean,” “Sephardic,” and “WASP” seems to have disappeared. The only identities left are ones like “black,” “white,” “asian,” and “hispanic” (though #spicywhite had its brief moment on TikTok). For that matter, the rich cultural fabrics forged by the numerous ethnic groups that fall under those categories make little sense to those who associate being “latinx” with a set of superficial stereotypes that can be easily captured in TikTok reels. Today’s pervasive rootless monoculture (with reductive cultural tropes sprinkled on top) can hardly be called “diverse.”

The fact that Harris doesn’t receive universal acclaim from black, Jamaican-, or Indian-Americans reminds us that identity is much more complex than we’d like to think, and that identitarian discourse has done little to help us understand and appreciate said complexity—especially when it comes to ethnicity.

This week in Compact

“The heart of Bidenism,” claims Christopher Caldwell, “lies in managing entitlements to the satisfaction of civil-rights lobbies and the economy to the satisfaction of tech and finance moguls…Biden needed his party’s base of finance and tech billionaires,” he continues, without whom he would never have been elected. Biden’s inability to satisfy his varied base led to a “donors’ coup,” says Caldwell, echoing the words of Sen. Marco Rubio, inevitably forcing him to back out of the race.

Despite talks of the possibility of Michelle Obama or Pete Buttigieg running on the Democratic ticket, President Biden endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris, much to the chagrin of many on the left. Zaid Jilani’s primary concern is that “Harris seems afraid to establish who she really is and what she stands for.” He argues that her chronic people-pleasing “ended up pleasing no one, and scuttled her once-promising presidential campaign. It is likely to do so again.”

In his first interview after his speech at the RNC, Teamsters president Sean O’Brien told Compact co-founding editor Sohrab Ahmari that he is committed to reaching “across the aisle and work[ing] with legislators who, regardless of their political affiliation, have working people’s best interests in mind…Partisanship,” he continued, “is not working. To get something really done for the American worker, both union and nonunion, we gotta get out of that thought process of one party line.”

Check out our latest podcast episode on Biden stepping down, Harris’s candidacy, and O’Brien’s speech.

Justin H. Vassallo takes us back to a time “when liberals fought free trade,” citing an example in the early 1970s in which left-wingers endorsed a bill that “threatened to discipline a restive business establishment intent on disabling the regulatory architecture of the New Deal order.” They “invoked an older American tradition in which the industrial arts’ were central to both civic life and individuality,” a sentiment which today is decried as “a blueprint for national populism and extreme isolationism.”

Panama magazine founder Pablo Touzon challenges the simplistic “far right” characterization of Argentina’s president Javier Milei. “Much of the progressive intellectual elite—most of them ideological supporters of Kirchnerism, the center-left formation that governed for 16 of the last 20 years in Argentina” Touzon writes, “prefers to think that Milei came from outer space,” and they bear no responsibility for his popularity.

As Venezuela approaches elections, Compact columnist Juan David Rojas asserts that “whether or not Venezuela devolves into further crisis will depend, in part, on international actors, notably the United States,” but more on Colombia and Brazil, whose leaders “have advocated for a parallel referendum on July 28 that asks voters to affirm a blanket amnesty for alleged crimes by both the [Maduro] regime and opposition.”

In her review of Anne Applebaum’s book Autocracy, Inc.: The Dictators Who Want to Run the World, Heather Penatzer writes that “Applebaum claims to offer a general account of autocracy in the 21st century, arguing that” a number of strongmen leaders “collaborate with each other to subvert democracy worldwide.” While acknowledging that it’s a fascinating read, Penatzer fears it is overly “paranoid,” offering a “dogmatic and Manichaean depiction of power.”

Meanwhile, Elon Musk has welcomed his twelfth child into the world, and his eleventh using assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Musk says he’s “doing [his] best to help the underpopulation crisis.” But Darel E. Paul warns that his “personal hoarding of the wealth generated by his investments undermines a more democratic distribution of male status…as more men are cast into relative poverty and have increasing difficulty both affording a child as well as even attracting a mate with whom to have a child.”

Out on the town

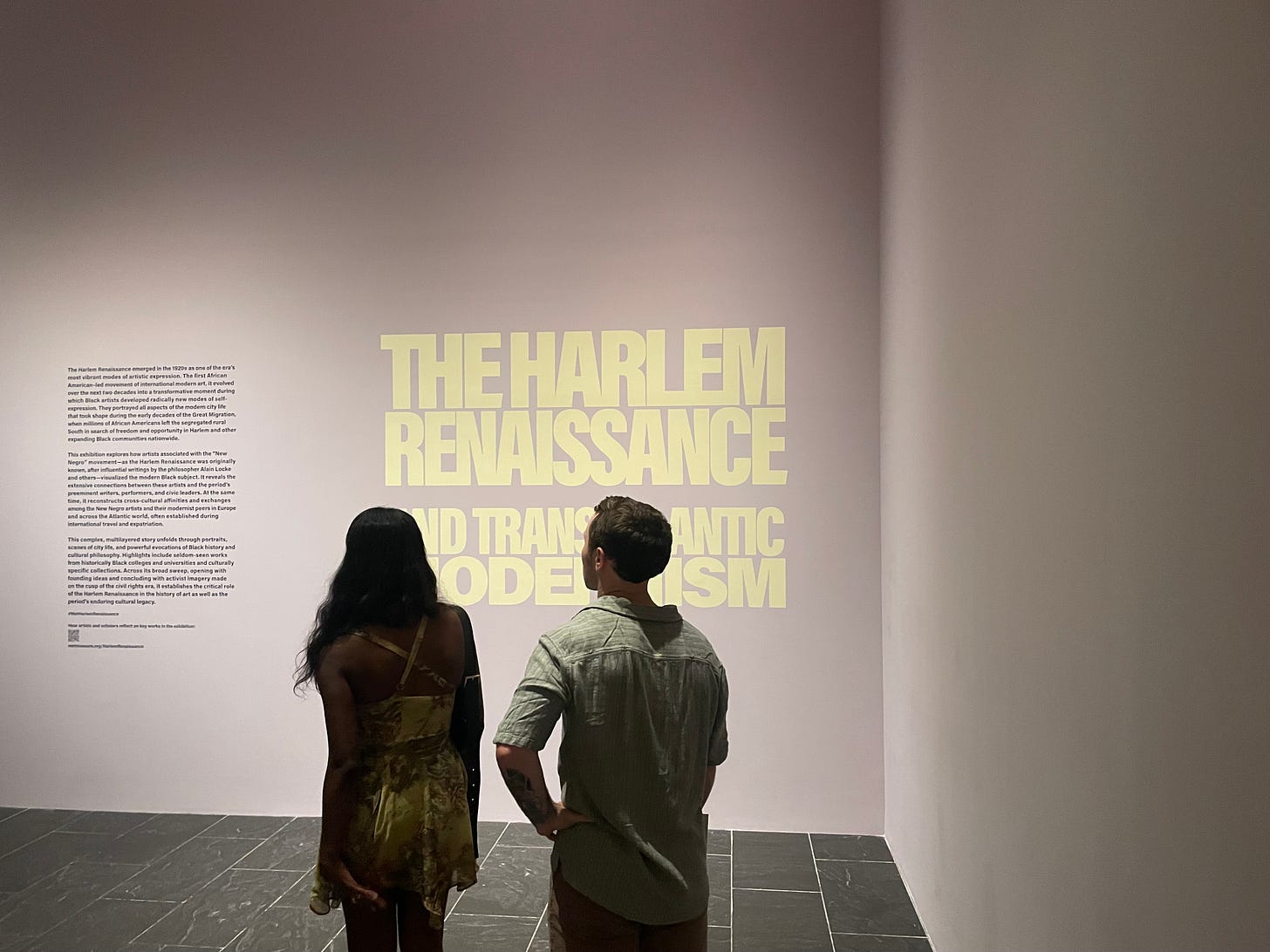

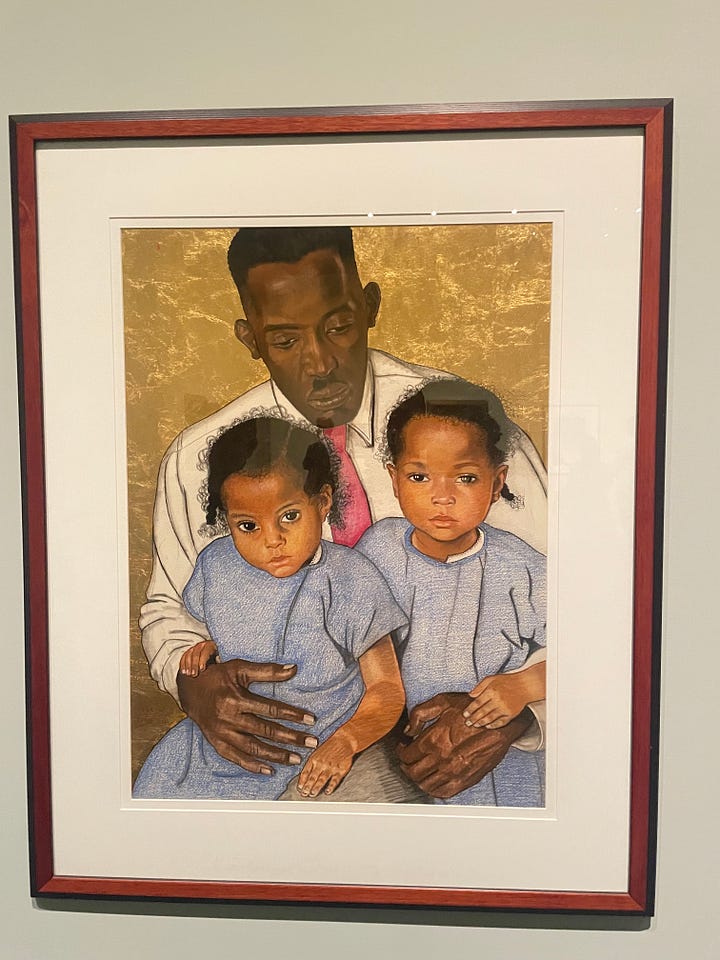

Last weekend, I had the chance to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art with Compact’s summer intern Dylan Partner and Germán Saucedo, whose work has been published in our pages. I made it a point to stop by the exhibit entitled “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” before it closes this Sunday, July 28th. Curator Denise Murrell aimed to capture “the comprehensive and far-reaching ways in which Black artists portrayed everyday modern life [in] the new Black cities that took shape in the 1920s–40s in New York City’s Harlem and nationwide in the early decades of the Great Migration.”

Among the collection were paintings depicting the life of these vibrant black enclaves of the era, portraits of the Renaissance’s major influencers like Langston Hughes and James Weldon Johnson, and relics like a first print edition of Zora Neal Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God. It also included pieces that captured the period’s intercultural exchanges, like Palmer Hayden’s French-style floral still-life that featured a bouquet of lilies alongside an African tribal mask, as well as portraits of “African diasporan subjects” by Europeans like Matisse, Munch, and Picasso. Before walking out, visitors are graced with a final wall-length panoramic collage of the various happenings on a Harlem block, including a creative Afrocentric rendering of the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary as it occurs inside an apartment building bedroom.

The captions featured alongside the pieces were refreshingly objective and substantive, unlike those found at other NYC museums (The Whitney, Brooklyn Museum) where the curation tends to regurgitate the identitarian script to the point of sounding algorithmically-generated. Though not covering over the realities of racial discrimination, the Met’s curators allowed these beautiful pieces to speak for themselves rather than presuming to tell spectators the “correct” take-aways. Unlike the antagonistic partisanship that Teamsters President Sean O’Brien warned leads to division and dead ends, this exhibit opens up a chance to broaden our cultural imagination and engage in real dialogue.

Go see it this weekend before it closes!