The Unbearable Fakeness of MAHA

RFK Is Now a One-Man Rebrand for the GOP's Bad Healthcare Policies

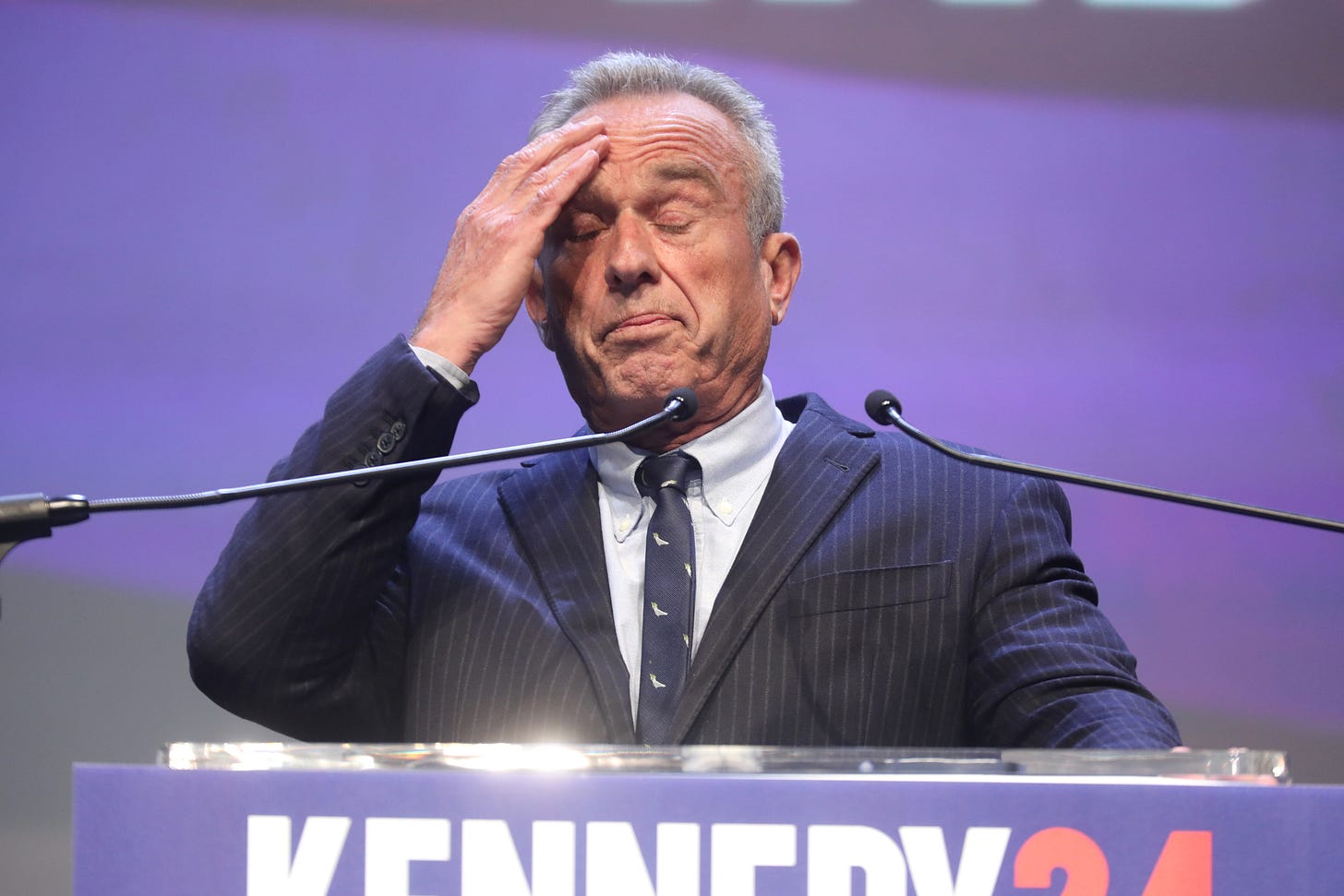

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.’s confirmation to lead Health and Human Services, with the support of all GOP senators but one, consolidates the rise of MAHA as a force within the unruly MAGA coalition. Many have asked what propelled RFK’s politics rightward; far fewer have asked why he has become, in short order, a beloved figure in the Republican Party. This is a more important question, because the evolution of the party in power has broader implications than one somewhat eccentric man’s political trajectory.

The enthusiasm for RFK in the GOP congressional caucus remains, on its face, somewhat baffling. To be sure, they converged over opposition to the Democrats’ Covid policies, especially vaccine mandates. (Though even here, it’s worth recalling RFK initially applauded lockdowns.) But almost all of the passionately held policy positions Kennedy has advocated for throughout his career—such as the regulation of chemicals and restriction of extractive industries—are still resolutely opposed by practically every Republican in Washington. His fellow cabinet appointees in Agriculture, the EPA, and elsewhere have promised to slash regulations on the food, fossil-fuel, and petrochemical industries, among others, and display the sort of coziness with the sectors they oversee that RFK has impugned as the source of the corruption he promised to root out as candidate and nominee.

When I have made this point on X, RFK fans usually respond by echoing what the man himself has said: President Trump and he don’t agree on everything, but they do agree there is a chronic-disease crisis, and are putting aside their differences to work on solving it. But by Kennedy’s own account, the sources of this crisis are dietary and environmental, and the regulatory agencies charged with preventing it have been irreparably corrupted. I’m not sure what it means for him to “agree to disagree” with the former food and chemical industry lobbyists staffing the relevant agencies in the administration in which he is serving—or rather, what it surely means is that the situation he has long decried will continue, with his blessing.

A revealing instance of the MAHA mystery is the enthusiastic support RFK’s nomination received from Sen. Ron Johnson (R.-Wis.). Before he entered politics, Johnson was an executive in the plastics industry; he maintained an ownership stake in the plastics company PACUR until 2020. People familiar with Kennedy and his followers will know the dangers of plastics are a major concern of theirs—especially microplastics that turn up in the human body, which RFK and others have hypothesized to be behind various negative health trends. During his presidential campaign, RFK assailed the Biden administration for “fail[ing] to confront the problem” of plastics and proposed a plan to address it, which included an “international plastics treaty” and measures to restrict and regulate chemical substances and incentivize recycling and low-waste packaging. This doesn’t, to say the least, sound like an approach likely to garner much GOP support.

So has newly minted RFK superfan Johnson had a change of heart about the industry that made his fortune? As a MAHA convert, does he want to regulate plastics along the lines Kennedy proposed? It is unclear, in part because neither RFK nor his high-profile boosters—such as the MAHA influencer Calley Means—seem inclined to interrogate their new GOP allies about any of this. It would seem Johnson’s affinity with RFK—like that of others in the GOP in the post-Covid years—derived initially from a shared skepticism of vaccines. But in the course of his nomination, Kennedy moderated his positions on this other signature issue to garner votes from pro-vaccine lawmakers. So even on that front, the relevant policy positions defining MAHA have become increasingly murky. Instead, the GOP-MAHA love fest now mostly consists of “won’t someone think of the children?” cant about the epidemic of childhood chronic disease, plus mostly policy-free encomiums to nutrition and exercise reminiscent of things Michelle Obama used to say, reliably attracting the ire and derision of Republicans at the time.

This vagueness is essential for holding MAHA together. Since RFK has backed away from or muddled his stances on key issues—especially his demands for increased regulation of food, drugs, and chemicals, at odds with the well-established GOP anti-regulatory agenda—Republican support for him now comes with no real concrete commitments. Ostensibly, Kennedy’s mandate is to “end chronic disease”—but again, according to the man himself, the sources of this crisis are mainly dietary and environmental, which means they fall under the rubric of agencies other than HHS, agencies that are now (as under past GOP presidents) led by pro-industry, anti-regulation stalwarts.

RFK’s willingness to compromise most of his long-time stances may explain how it has become possible for Republicans to embrace an environmental activist, but it doesn’t really explain why it is useful for them to do so (beyond getting to have a Kennedy in their ranks). The most likely answer has to do with the toxicity of the GOP’s brand on healthcare. When Donald Trump infamously alluded only to “concepts of a plan” to replace Obamacare in a debate with Kamala Harris last year, he had good reason to be vague: His party garners abysmal ratings in this area, and most of the specific policies Republicans propose poll even more poorly.

What RFK offers the GOP, therefore, is a rebranding opportunity on a policy area the party has struggled to address. Now that RFK’s longstanding regulatory proposals have been sidelined, MAHA consists mainly of lifestyle advice consistent with the “personal responsibility” vision of health long promoted by the party. It is also premised on the idea that healthcare costs can be reduced by reducing people’s likelihood of developing chronic illnesses—surely true in theory, but difficult to achieve without the sorts of “nanny-state” interventions Republicans have always opposed. Hence, it is more likely the party will seek to reduce federal outlays on healthcare in the same way it has long done: by forcing patients to have more “skin in the game,” i.e. to take on more of the costs of their own care. That is the takeaway of the MAHA zeal of another recent GOP convert, Rep. Chip Roy of Texas, who penned an op-ed encouraging his fellow conservatives to support RFK’s nomination. Around the same time, Roy also released a plan for “healthcare freedom,” which gives a MAHA overlay to a collection of free-market nostrums that have been floating around the conservative think-tank world for half a century.

MAHA proponents make plenty of correct observations. The US healthcare system is indeed riddled with perverse incentives; many of our most pressing health problems result from dietary, lifestyle, and environmental factors that medicine itself doesn’t address well; Big Pharma is corrupt and corrupting, not least of the government agencies overseeing health; and so on. But by being absorbed into a party that continues to hew to the most radical version of the market-based approach that—although no Republican will admit it—informed the most damaging parts of Obamacare, these insights will now serve as new pretexts for pursuing the party’s zombie austerity agenda. If Medicaid spending, as RFK remarked during his hearing, hasn’t stopped the chronic disease crisis, perhaps best to simply decimate its budget; if regulatory agencies haven’t prevented microplastics from infesting our bodies, perhaps better to abolish them altogether. The sad culmination of RFK’s career may be to provide a new cover for this nihilistic project.

This week in Compact

It’s been a wide-ranging week of coverage at Compact:

Christopher Caldwell’s latest column is an authoritative account of Germany’s AfD and the change it is forcing on the nation’s political order in the run-up to the next elections.

Historian Jay Sexton revisits the original Monroe Doctrine, which Trump’s administration has invoked as a precedent for its foreign-policy posture, and finds it wasn’t nearly as coherent or as successful as its present-day admirers imagine.

Juan Rojas’s latest column scrutinizes Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s tour of Latin America and finds evidence of a turn toward a more pragmatic, less ideological approach.

D.L. Jacobs argues that the new AI Cold War between the United States and China distracts from a larger issue: the drive for profit is holding back the technology’s true potential.

Columnist Valerie Stivers surveys the career and life of Japanese writer and self-described “aesthetic terrorist” Yukio Mishima and finds much that is relevant to the current crisis of masculinity.

In response to Donald Trump’s proposal for Gaza, Heather Penatzer looks back at the grim precedents for mass population transfer and finds that even leaving aside moral qualms, it is difficult to regard any such efforts as a “success.”

Audrey Pollnow reviews Ross Douthat’s Believe and makes “the erotic case for God.”

Leighton Woodhouse examines the class politics of DOGE.

Gabriel Rossman rescues the useful social-scientific concept of social construction from those who overestimate its extent and those who attempt to dismiss it altogether.

Thanks for reading! Please consider subscribing to the magazine if you don’t yet.

You're confusing old school chamber of commerce Republicans and uni party types like McConnell with newer types like Vance and Gabbard, and the much larger group of people from the "open source right", including many social conservatives that have been paying attention to health and welfare for years.